Arch Out Loud: Designing a Surface Marker for a Geological Repository of Nuclear Waste for the Benefit of Our Children

In October 2017, a group of researchers in archaeology at Linnaeus University submitted an entry into the arch out loud competition for designing a Nuclear Landmarker at the site of the Waste Isolation Pilot Plant (WIPP) in Carlsbad, New Mexico.

We had been working for the past six years in close collaboration with the Swedish Nuclear Fuel and Waste Management Co. (SKB) addressing questions about long-term communication in relation to final repositories of nuclear waste. It seemed the competition was an opportunity to get some of our ideas out there.

Our entry draws directly on on-going research in the Heritage Futures project which seeks to understand and innovate heritage practices for the future from the perspectives of heritage studies, archaeology, cultural geography and social anthropology. Nuclear waste is a wonderful case-study for ‘heritage futures’ as it is one of the most high-profile legacies of our time for the distant future. It should therefore not be surprising that SKB is one of more than 20 project partners in this major AHRC-funded research programme led by Professor Rodney Harrison and based at University College London.

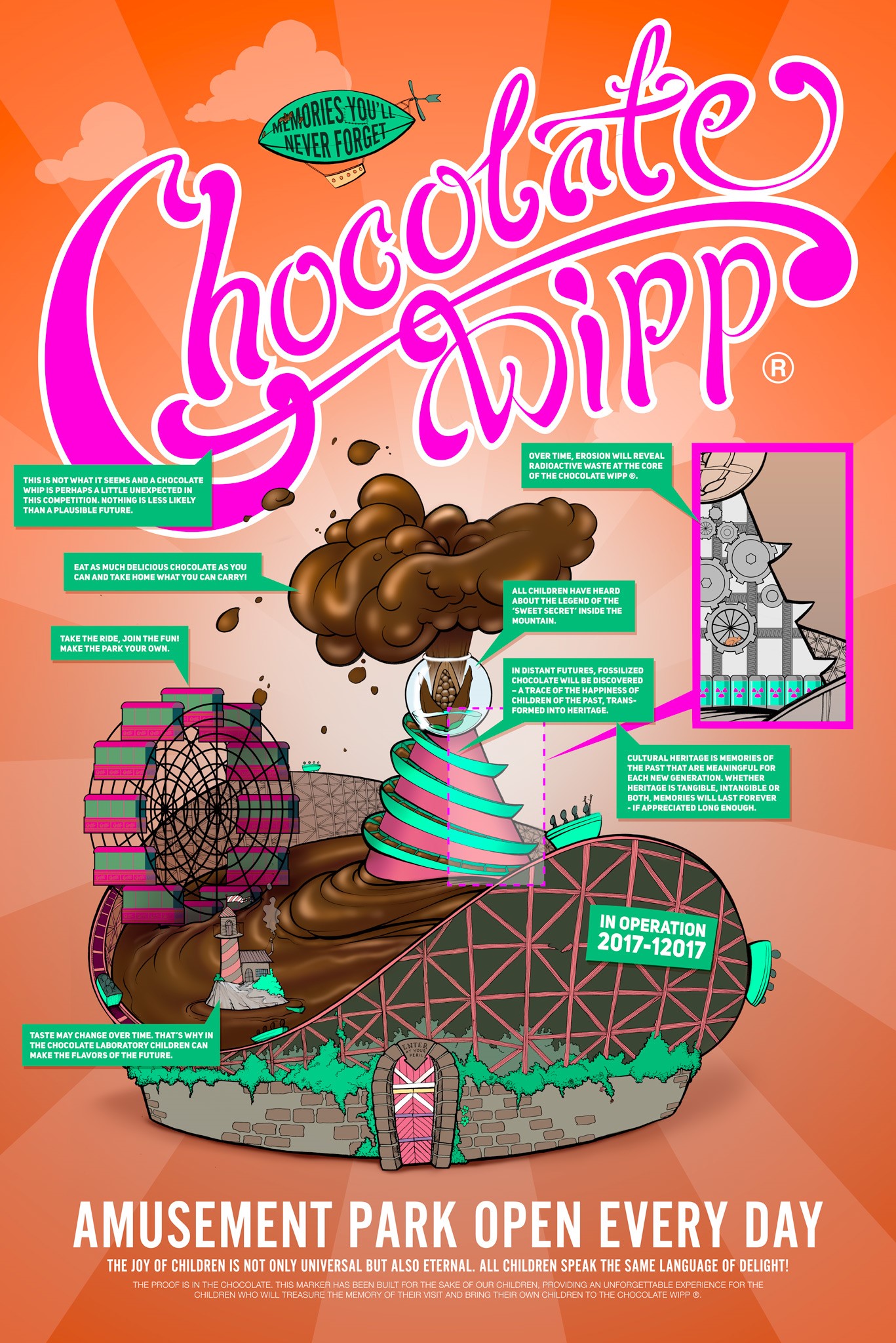

The nuclear marker we proposed is called Chocolate WIPP and represents an amusement park. The entry was drawn and creatively enhanced by the archaeologist and graphic-designer Daniel Lindskog who is a former student at Linnaeus University.

The title Chocolate WIPP, as well as the finished design, suggest that the approach we have taken is somewhat different compared to what one might expect in such a serious context. We emphasized notions of fun and entertainment, adopting a light-hearted attitude throughout. After all, nothing is less likely than a plausible future, as David Lowenthal once put it – and that can apply even to the competition itself and the underlying expectations of what would be submitted.

The design takes the common claim literally that the heritage is preserved for the benefit of our children and grandchildren. Whereas most work about nuclear waste, and indeed the entries that won prizes in the competition, are directed at adults, we wanted to impress children with memories they wouldn’t be able to forget and thus keep the memory of the site alive. Hence the focus on chocolate and fun.

Our approach was informed by recent work of Sarah May who is a Research Associate in the Heritage Futures project. She is arguing in a forthcoming paper that in a heritage context the future is often domesticated through infantilization which allows present-day adults to take responsibility and express care in order to relief their own anxieties. In contemporary society, the future is sacralised in the same way as infant children are sacralised. The Chocolate WIPP challenges that thinking by providing what children of the future might actually appreciate rather than what adults think they ought to appreciate when the children will have become adults themselves.

The focus on children also helped us solve the conundrum of how to create a marker that would be understandable and meaningful for up to 10,000 years, as specified in the competition brief. It is easy to think that the joy of children is not only universal but also eternal, as all children speak the same language of delight! In order to allow for some modifications in taste, the design includes a chocolate laboratory where children in the future can create their own flavours and thus upgrade the chocolate whip to preferences of different time periods.

The Chocolate WIPP itself will not be forgotten as long as children love chocolate. We are however sceptical that, in 10,000 years, anything we create today will actually be understood in the way intended. It is essential that each future will be able to give its own meaning to what they find in their surroundings. Even chocolate may eventually fade into history.

More likely than not, the park will not stay open for 10,000 years – despite the best chocolate memories ever created. Physical erosion will eventually reveal not only fossilized chocolate, a trace of the happiness of children of the past, but also the radioactive waste that is at the core of the mountain. This heritage will remind unsuspecting visitors of the way in which this place has been associated both with fun and with responsibility for something potentially very dangerous – which adds another dimension to the rules of the park that you should “take care of your valuables at all times” and that “all rides are taken at your own risk”.

At its core, our entry expresses the idea that nuclear waste will be cultural heritage of the future. Memories of the past, as supplied by childhood visits to the Chocolate WIPP, will be meaningful for each generation. They will pass on those memories to their own offspring by taking them there too. In this case, the heritage is composed of both tangible aspects (the site itself, the chocolate to take home) and intangible aspects (the taste of the chocolate, the tradition of going there). There is even a legend about the “sweet secret” hidden inside the mountain which parents are passing on to their children. As often as not, there is some truth in the stories we tell our children about places in the landscape…

Reference

May, Sarah (forthcoming 2018) Heritage, Thrift, and our Childrens’ Children. In: C. Holtorf and A. Högberg (eds) Cultural Heritage and the Future. London and New York: Routledge.

Cornelius Holtorf, Anders Högberg, Daniel Lindskog