Exploring Uncertainty

Doing fieldwork on distant futures isn’t always straightforward. My main field site is the English Lake District, but no place exists in isolation. While I explore landscape construction, reconstruction and rewilding in the Lake District, other places also feed my thoughts. Voices from the Lakes follow me too. Here’s a glimpse.

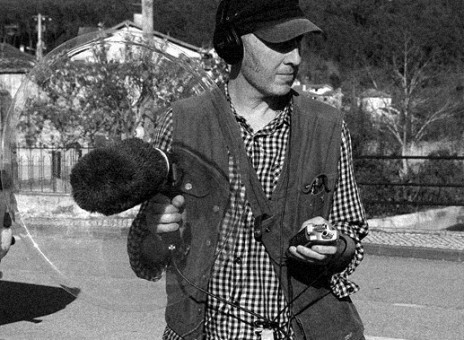

In this project we are using film as method, to improve our ethnographic work and sharpen our analysis. I find this challenging. The camera equipment can feel intrusive when working with new participants. My usual interaction is quite chatty, so it’s hard to get good ‘talk to camera’. But it’s great to try new things and I value the perspective even small amounts of filming have given me. What’s more, the editing process, like the writing process, gives a different angle for analysis. All of this also encourages more interdisciplinary working as well because film making is, like archaeology, always a team process.

In this case our creative fellow, Antony, wanted to encourage me to make something of footage I’d captured like field notes. He was interested in how contrasting field sites illuminate each other. We worked together editing, bringing in footage, field notes, quotes from participants. I’m used to making explicit arguments, but wanted to leave space for the viewer to draw their own conclusions. The process of editing built the arguments in my head as much as the arguments drove the editing.

I can’t resist some words to go along with the video – the urge to draw out the themes is too strong.

Representation, reconstruction, constructed landscapes; these are perennial themes in heritage. Heritage has an uneasy relationship with reproduction, because it surfaces the troubled notion of authenticity. The 3D print of the arch from Palmyra is an accurate (if scaled down) representation of the arch at a moment in time, but its de-contextualisation makes it uncanny. Gabe Moshenska rails against the colonialism he sees in this event which many see as rescuing Palmyra.

In the Lakes, the question of authenticity is a matter of practice. While Ruskin celebrated the sublime beauty of its glaciated mountains, he was aware of it as a cultural production. The current World Heritage Site nomination is as a cultural landscape, with an acknowledgement of the centrality of sheep to that culture. But sheep are increasingly less profitable, especially upland sheep like the Herdwick, which are particularly important in the Lakes. The rewilding movement proposes an alternative future for these fells, based on a different sense of authenticity as springing from place unmediated.

In Palmyra, the Lakes, Trafalgar Square and even Greenland the question always comes back to audience. The practices of landscape and heritage in Palmyra are equally as complex as they are in the Lake District, but when we pull out the pieces we grieve the loss of, authenticity is framed for us not for the residents. The boulder with graffiti “Qatar” on the shore of Thirlmere reservoir reminds us that World Heritage cuts both ways. Andrea Meanwell says that one of the reasons that ‘offcomers’ feel a right to pronounce on how her land should be used is because it is a National Park – so people feel that it is in some sense a place that belongs to everyone. (see her new book) Is our nationality also produced for an international audience?

World Heritage seeks to preserve the Outstanding Universal Value of designated places in perpetuity. The arising values of those places in networks of meaning are less easy to contain. What is it that we are doing for future generations?

SHORT LAKE1 from Heritage Futures on Vimeo.