Landscapes in Limbo

Two years into a four-year involvement with the boundary-pushing research project Heritage Futures, I’m taking stock, in a self-reflexive manner, of what’s emerging within my field of view, and of what are the germinating seeds for developing site-inspired creative responses or activations – in three ‘landscapes in limbo’.

In the first part of these reflections, I’m primarily focussing on the three edgeland locations that form the study sites for the Transformations theme of Heritage Futures: Orford Ness, Suffolk (‘post- military/coastal change’); Cornwall China Clay area (‘post-mining’); and Côa Valley, Portugal (‘post-agricultural/rewilding’). Whilst these form the main geographical juxtapositions, other situations have become enfolded into my scope, and the scope of the research project, e.g. Hawai’i (sacred landscape and indigenous tensions) and Palmyra, Syria (examining associations and connotations of an ancient stone archway and its globe-trotting 3-D replica).

After a series of visits to connect with, document and contemplate the three primary sites over the past two years, I’m at the stage of assessing what affinities and creative resonances have shown themselves to this puzzle-ing student and imagineer, who has landed in these places wearing the hazy cloak of the geo-poet, assembling the poetic from the gleanings and fossickings under stones, from beneath the bark of trees, and out of a myriad of minds and desires.

I’m interested in the ways in which these settings are being viewed and activated as intentional and experimental models, with potential for replication elsewhere. Together with the human, there are the non-human ‘actors’ – vegetation, animals, erosion processes (this also involves vegetation). These are limbo-landscapes, not static, but freed (temporarily?) from many of the strictures of human industry, commerce, war-making. For the non-human actors, or agents, there is a ‘being-ness’ of modus operandi; to move, to grow, to creep…

I’m interested in the ways in which these settings are being viewed and activated as intentional and experimental models, with potential for replication elsewhere.

Rewilding

“Everyone is talking about rewilding at the moment. The debate around it is shaking up the conservation sector and public interest in it is huge, with a growing movement of people advocating the restoration of our degraded ecosystems.” [1]

In this sector of the Heritage Futures programme, ‘rewilding’ has, from the start, been one of the the primary lenses through which all the explorations – eco-creative or academic – have been viewed. Alongside this complex and nuanced term, there has emerged, for me, a bundle of related terms – recovery, rehabilitation, ecologically restorative processes, regenerative land-use, and more.

The key in all this is an emphasis on process (and future potentials). Future-looking processes, and processing, are central in my field of view, but these are not divorced from the past, nor divorced from letting-go, or the necessity of formulating cultural/social healing.

Recently, Caitlin DeSilvey, a co-investigator in Heritage Futures, took part in a BBC radio debate which addressed these issues, and shared reflections on –

“…relationships and unfolding processes instead of permanence and fixity…”

“letting-go can let us be human in a particular way”

Caitlin DeSilvey (BBC R4, Thinking Allowed, 26 Jun 2017)

One of my own core concerns is with emergence and ‘energy’ – vital forces – human mental forces, human inspirations and passions. I’m interested in how these sit and fit alongside connection, empathy and understanding.The complexity and contested nature of all these situations emerges in views such as this:

“If you let nature take its course you will be covered in foliage and dirt, realistically; that’s not a very attractive situation to be in…and that’s a very human way of seeing, it’s not very realistic.”

Tiffany Jenkins, sociologist & cultural commentator (BBC R4, Thinking Allowed, 26 Jun 2017)

Personally, I look towards some more enduring, timeless voices:

“What would the world be, once bereft

Of wet and of wildness? Let them be left,

O let them be left, wildness and wet;

Long live the weeds and the wilderness yet.”

G. M. Hopkins – Inversnaid, 1881

Other encountered voices (in particular in the China Clay lands of Cornwall) speak of the – essentially unwanted – ‘overburden’. The fields, soil, homes and the holistic richness of cultural landscape were all literally a ‘burden’ or obstacle in getting at the clay resources; in ‘winning’ the clay.

In the radio discussion to which I’m partly responding here, there were some interesting dialogues about (anthropologically viewed) relationships, conversations, experimentation, in contrast to a “zero-sum” game of winner+loser. This very much gels with my approach (in a creative ethnographic style) of seeking and building relationships, revealing relationalities and highlighting rhyzomic/mycelial connections. Creative experimentation is about probing; seeking that which intuitively inspires one; then using that as a guide, going forward.

“Futures are designed & built of constellations – things, persons, people, practices – in specific moments.”

Heritage Futures and Future Heritages – Inaugural Lecture by Professor Rodney Harrison, June 27 2017 (online recording)

This is very pertinent to the topic of rewilding in these places. In all three sites, people (professionals mainly) have expressed the view – or belief – that rewilding will happen anyway, without any human intervention, or that it is underway already. In this mode of thinking, the interventions are – for instance in the Portuguese case – intended to provide protected refuge zones, or safe havens, for selected threatened species, thus giving assistance to natural processes. For the ecological stewards of the Côa Valley area, there is a pressing urgency. Some key (loved and admired) species may disappear before the re-establishment of biodiverse richness in this landscape, and its trophic cascades [2].

There is some distinction between the subtle affinities, resonances and dissonances that I sense (or intuit) in – or between – these three study landscapes. When asked recently to make a small selection from my photographs to represent each site, some interesting themes emerged. A kind of distillation has occurred – not just of a profusion of images, but of my thinking about some core relationships to site and place. The exercise has turned out to be a useful creative-research tool. This image selection process has revealed to me a previously occluded pattern, or mesh of connective tissue.

Cornwall China Clay area

The photo-set from Cornwall clusters around re-vegetation growth – recovery, creep, slow, inexorable returning. Many of the the buildings are transforming to damp, dripping mossy caverns; the raw wounds of the stripped granite gradually being re-carpeted.

Here, we are encountering the living skin – ‘Soil and Soul’ [3], vegetation, animals, people, and a vital materiality of human and non-human forces.[4]

In this Cornish mining area, what is presenting to me is the fecund force of the self-regeneration of ecology, of vegetative growth, of a kind of scab-formation on the raw, bleeding wounds. On the UK Ordnance Survey maps, the active working zones of the clay extraction were, and still are, depicted as blank ‘white spaces’, their features being too ephemeral to fix in map form. The creation of these white spaces involved a peeling back – or scraping away – of this skin, the overburden. A violent wrenching away of plants, roots, soil, regolith. And villages, graves, community and culture.

‘Rewilding’ or not, the creeping moss, vines, ‘weeds’ are on the move. The healing of the deep gouging scars is underway, and the scale is much bigger, more powerful than any of our human efforts to plan, engineer, imagineer or ‘regenerate’. In the future, there will be new eco-towns, leisure activities in the flooded pits, maybe vineyards and solar farms on the tips, monkey-puzzle plantations, Eden-style destination projects, but the slow green creep will gradually cover and heal all these white spaces. At times this seems like a Triffid-like force, persistent and determined. This is true of many post-industrial landscapes, but especially so in this moist, Atlantic-rain-swept semi-tropical land. I am reminded also of some descriptions in Ballard’s work of ‘speculative fiction’, The Drowned World (1962).

“The sun was still hidden behind the vegetation on the eastern side of the lagoon, but the mounting heat was bringing the huge vicious insects out of their lairs all over the moss-covered surface of the hotel…In the early morning light a strange mournful beauty hung over the lagoon; the sombre green-black fronds of the gymnosperms, intruders from the Triassic past, and the half-submerged white-faced buildings of the 20th century…”

The answer – or the future – is surely to embrace the ivy, lichen and moss?

Resistance is futile…

The deep-time, time-lapse rhythm is one of ebb and flow of vegetation. Often the destructive force has been the advancing ice and tundra conditions. Paradise lost; paradise regained. Vegetative entropy.

“In our fairytales, beanstalks rise monstrously” [5]

In a real, but also poetic sense, this can be seen as ‘chlorophyll returning’, (here too is a connection to the topic of ‘solar-energy futures’ in this land).

The healing of the deep gouging scars is underway, and the scale is much bigger, more powerful than any of our human efforts to plan, engineer, imagineer or ‘regenerate’.

Weeds

“I want all my friends to come up like weeds, and I want to be a weed myself, spontaneous & unstoppable.” Roger Deakin

Richard Mabey writes of “outlaw plants”[6]

“weeds vividly demonstrate that natural life – and the course of evolution itself – refuse to be constrained by our cultural concepts…”

“they are the boundary breakers, the stateless minority, who remind us that life is not that tidy.”

The contemporary global social challenges of managing waves of migration and refugees is bound up with attitudes to invasive plant and animal species. Across these domains, there is a shared terminology, seen in concepts and beliefs such as ‘alien’, ‘foreign’, ‘purity’, ‘colonisation’, ’struggle for resources’ and ‘indigeneity’ etc.

Orford Ness

As a segue into the next case-study site, there is the case of one particular weed species. During and after the London WW2 ‘blitz’, rosebay willowherb (aka ‘bombweed’, or ‘fireweed’; Chamaenerion angustifolium) flourished amid the city’s rubble, thriving on the disturbed ground. This plant is also very widespread on Orford Ness, Suffolk – the location of decades of aerial bombing training and weapons testing. Vegetation is clearly a significant agent on the shifting shingle spit of Orford Ness, but a developing creative narrative also embraces the formal and abstract character of some residual and historic structures.

Here also, the vegetation is active, encroaching, even breaking apart the granular fabric of the enormous concrete ‘pagodas’ (pictured above), but this vegetative impulse has always existed in a precarious balance with the mobile, shifting shingle – long before any human influence. A violent storm blows up, and large areas – volumes in fact – of the loose unconsolidated land get churned up and re-sculpted. The defunct lighthouse, iconic and locally treasured, lies closer and closer to the retreating shoreline every day. Over the centuries, three predecessor lighthouses have been lost to the sea, and this last one will succumb to a similar fate very soon. At this location, we are in conversation with a very dynamic, fluid land-sea interface. This is the essence of the future that is emerging here – a moulding and remoulding by the relentless forces of the sea. The power of the sea, of storm and tidal rhythms, encounter the slower fluxes of stone, shingle, flint. It’s a dance.

And no-one lives on the ‘Ness’.

In a way, this fact gives it an anomalous character, out of tune with most other UK landscapes; a place that brings to mind the wording of the USA’s Wilderness Act of 1964, which defines wilderness as area

“untrammeled by man, where man himself is a visitor who does not remain.”

The Ness is then a curiosity, an exception. Here exists no residential community (apart from the single ranger on duty at night). Yes, there are National Trust visitors, occasional fishermen (supposedly), Nicholas Gold – the new owner of approximately half the spit, and his acquaintances. At times, there are special residential workshops for those who are fascinated with such a sparse, elemental, crumbling place. But it is ‘home’ only to the plants and animals – the latter which properly occupy the ‘ness’ once the human visitors and worker have departed at the close of day.

To many, the lure of Orford Ness is clearly strongly felt. Perhaps it even has some association with that which has been noted in relation to those North American wilderness areas – repositories “of values that people once invested in the monarchy or the church[:] moral purity and social stability.”[7]

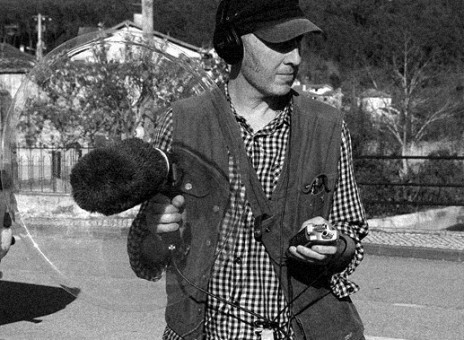

As Chris Watson related to me (in the ‘Bomb Ballistics’ building, in July, 2016)

“Orford Ness is a place in transition…it always has been…[humans] are here over a very transitory time, compared to the action of the North Sea on this part of the Suffolk Coast, and the coastal erosion, and the currents that sweep this coast…people relish coming to the edge of somewhere, the threshold of landscape and seascape…a place out of our control…quite alien and strange…”

Maybe it’s the starkness of the landscape – or the fluidity?; or perhaps it’s that these building still have social and political resonance, and ‘vibrant’ energy? These temple pagoda shapes, the square apertures of some remnant structures with onomatopoeic names like ‘bomb ballistics’.

(Globally, we are still tethering on the edge of an atomic (war) abyss; this is one of the sites where some of the technology was developed and tested).

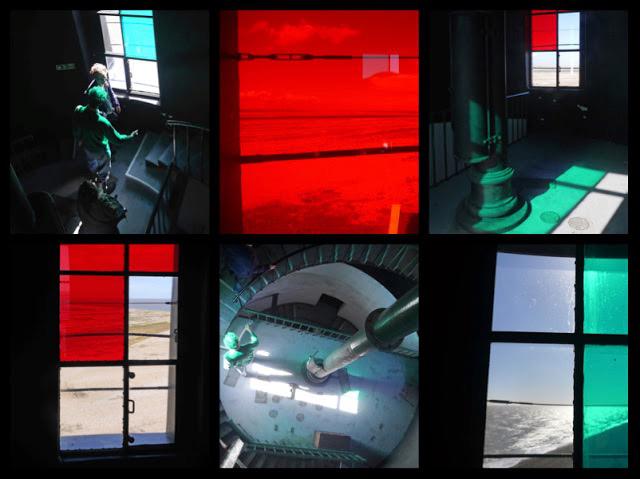

Orford Ness – colour and formality

For me, the photo-selection that emerged was somewhat surprising. Perhaps it is the raw starkness of the landscape, but I find myself inspired by some of the ‘pure’ abstract forms and colour symbolism and signals. A pared-down simplicity. The photo-set suggests a focus on geometric architectural form; building /structure – plus the attention to colour – in an abstract way, especially in the ‘sector lights’ of the lighthouse. Perhaps in this instance, I am drawn – romantically – to the poetic idea of a light going out, and in a blaze of colour, firework-like? Colour and form; structure and geometry. In a way, this is the antithesis of the informal, organic theme in Cornwall. A doomed lighthouse has a magnetic attraction, of course, but I am intrigued in particular by these red and green glassed ‘sector’ windows:

“Since then [1914], a red light – visible for 14 nautical miles – has shone north to mark the Sizewell Bank….the green light shines over Hollesley bay, for 14 nautical miles and the red shines over whiting hook and whiting bank visible for 15 nautical miles.” [8]

Structures, form and colour? These are all clearly human interventions. Partly they signify control over organic fluxes. The return and reestablishment of organic flux is evidenced in the stalagtites I encountered in an abandoned building, but also there are other resonances and these relate to the atomic past, the testing and development of weaponry; heat, molten glass, is one of the byproducts, or results. The geometrical building forms and red-green lights, are oppositional, not just to organic revegetation but also to the storms and the sea, tides and wind processes. Oppositional to the flux and endless dynamic change. In this way they hark back, at least poetically, to the pyramids of Egypt and Mexico. They are not about the dance with life and the energy of the universe, but are statements of otherness.

Orford Ness was one of the hotspots for coastal erosion identified in the 2015 National Trust’s Shifting Shores report [9], in which there is acceptance that certain land areas will soon be engulfed by the sea, a process of managed decline. There is ongoing pressure for the local community to be involved in adaptation responses and strategies that reflect local interests. In 2013, Trinity House offered the lighthouse for sale, leading to its purchase by Nicholas Gold, and establishment of a charity (Orfordness Lighthouse Trust) to manage it. Mr Gold and the Trust are now neighbours. In a submission to the National Trust AGM (2014), Gold explained that the encroaching sea put the lighthouse at risk of collapse. The Orfordness Lighthouse is an iconic feature of the East Anglia coastline which he felt should be protected from ruination.

Côa Valley, Portugal

Emerging from the Portuguese photo-selection, the theme is clearly ‘people and animals’…and also fire (which here features intimately with people and animals, most directly through the activities of shepherds).

And this isn’t a surprise. I have felt deeply connected to the place from my first visit (and previously on an artist-residency at nearby Binaural-Nodar). Over a series of visits, I have been shadowing some chosen individuals. There is a deepening of relationship, and a dialogic companionship. This state is necessary for the type (or timbre) of recording of voices and visuals that I envisage. Thus far, the relationships formed in this landscape outweigh anything within the other two sites. Of course there are people with visions and plans for futures at all three sites – ranging across strategic/organisational, community groups to impassioned individuals. At Orford Ness, there is for instance lighthouse-owner, Nicholas Gold; the ‘official’ visions of the National Trust; and community activism in relation to the lighthouse. In Cornwall, there are long-running strategic planning visions; the strong influence of the ‘owners’ (of much of the post-mining land) Imerys; plus individual perspectives too. But in Portugal, I’m finding the intensity and motivation of the individual and group visions of ecological necessity (for protecting species and providing linked ‘stepping stones’ refuges and boosting food-chains) drives forward a strategy – a recovery plan for threatened animal species (and it is hoped, by extension, an eco-futures socio-economic recovery).

This is in counter-balance to a pervading sense of pessimism – amongst the older population in this landscape and villages. They are in the majority as the young have left. They don’t, on the whole, envisage a positive future. Their familiar way-of-life is in terminal decline. They see a human/social retreat from the land, and no future for their families, no real human vital future. Most are at arms length from the eco-minded visioning – the eco-tourism, the environmental education, the plans for protected areas, the wildlife futures. In their eyes there is further threat to the way of life – e.g. to the hunting traditions, the practice of burning the ground cover to benefit the grazing of sheep- and what they see as the support (by the ecologists) for old enemies – the wolf, and the wild boar. It has not been a strong part of the farming tradition to have empathy or sympathy for wildlife (such is the western way…). The farming livestock future is declining. There is some remnant hunting tradition, but this too is in conflict with the conservationists.

But people and animals link also through the past – the past of many timescales.

Pigeon-houses of the Côa Valley have in some ways a quality that echoes the lighthouse discussed above – round, white, prominent in the landscape. They are clear geometric impositions on the landscape, defiantly occupying bluffs, headlands, promontories. They are almost like acupuncture points throughout the Côa Valley. These structures point to a complex intimacy between species – human & pigeon. But also a dependency on a certain land-use – the growing of crops on which the pigeons would feed. Now, there are few fields of crops; and consequently no occupying pigeons, despite the efforts of the ecological organisations Palombar and ATN wishing to boost the food supply for the Egyptian vultures.

The shepherds – the few remaining (like Lionel, pictured above) – who will not be passing on the livelihood to their offspring; who say there is no future here for shepherds. Yet who are part of this land like no-one else. They inhabit its subtle changes. In the encounters with these situations, my stance is geopoetic, and my interest is in the dynamic links between people and place (landscape, ecology, buildings, objects), viewed through the lenses of landscape recovery and rewilding. The creative and collaborative research processes have involved undertaking imaginative journeys together with researchers, local individuals, community representatives, environmental stewards, museum staff and many more. Eventually, assemblage works (film-poems & immersive sound+light+visual installation works) will be presented in locally distinctive buildings of heritage importance. Woven into the mix will be personal stories and future-visions, rooted in the place, but with a universal resonance. The aim is a metaphorical weaving of hopes, visions, tensions and possibilities in these landscapes of decay, renewal and rewilding. I’m seeking to access the both knowledge and undercurrents; resonances and dissonances; antagonisms and compromises. As in biological morphogenesis [10], there are opposing signals; some activating and some deactivating growth and change. An evolving dynamic new shape is what results.

[PART 2 of this dispatch to follow shortly]

Notes

[1] http://www.theecologist.org/blogs_and_comments/Blogs/2989124/introduction_to_rewilding.html

[2] Aldo Leopold is generally credited with first describing the mechanism of a trophic cascade, based on his observations of overgrazing of mountain slopes by deer after human extermination of wolves. Leopold, A. (1949) “Thinking like a mountain” in “Sand county almanac”. Also see here: Google Books link to Feral:Rewilding the Land, the Sea, and Human Life, by George Monbiot, 2014.

[3] Title of a 2001 book by Alastair MacIntosh: Soil and Soul; People versus Corporate Power

[4] Referring to Vibrant Matter: A Political Ecology of Things (2010), by Jane Bennett

[5] Eating Dirt: Deep Forests, Big Timber, and Life with the Tree-Planting Tribe (2011), Charlotte Gill

[6] Weeds – the Story of Outlaw Plants (2010), Richard Maybe

[7] American Wilderness: A New History (2007), Michael L. Lewis

[8] http://www.orfordnesslighthouse.co.uk/history, http://www.worldwidelighthouses.com/Lighthouses/English-Lighthouses/Trinity-House-Owned/Orfordness

[9] https://www.nationaltrust.org.uk/documents/shifting-shores-report-2015.pdf

[10] Morpho-genesis is the process by which an organism, tissue or organ develops its shape. Morphogenesis is driven by various cellular and developmental processes including cell proliferation, differentiation, apoptosis, cell migration and cell adhesion.

ALL IMAGES: Antony Lyons