Oranges and Lemons: When is the Heritage of Diversity?

“From an artificial stone base at the corner of the site rises a tubular steel structure, approximately 29 metres tall, its form intended to recall that of a minaret; it was added in 2009 and (at the time of the present evaluation in 2010) is too recent to be of special interest.”

The above excerpt from Historic England’s list description for London’s Brick Lane Jamme Masjid (Friday mosque) asks difficult questions about how past and present are integrated in heritage management, and whether we are as bold in what we do with heritage as in what we say that heritage does. This post explores the heritage of diversity wrapped into the idea of the East End of London.

An Uber driver recently asked me where I was from. I’m British, and – give or take a year or three – I’ve lived in London since I was 18. So you’re a Londoner, he said. I said I could never quite bring myself to say it. It turned out we were nearly the same age, and he came to London from India the year before I moved here. But he laughed as if it was a preposterous suggestion that he might be a Londoner. There’s a sort of mythical Eastender and an unspoken whiteness in the idea of the Londoner – born within the sound of Bow Bells – and my grandparents were, but they moved out, and I’m far from it.

Triangulate three of the churches in the old oranges and lemons rhyme – St Leonard’s (“when I grow rich, say the bells of Shoreditch”), St Dunstan’s (“when will that be? Say the bells of Stepney”) and St Mary-le-Bow (“I do not know, says the great bell of Bow”) and we’re just about in Spitalfields. It has all of London: plague pit; mainlines and branchlines and the new Crossrail passing underneath; glittering skyscrapers, controversial wrought-iron columned market redevelopments; Jack the Ripper tours and Hawksmoor churches; 18th century weavers’ houses and curry houses; hipsters and spivs and hawkers.

Recently, I had cause to get familiar with all the area’s listing descriptions. This little patch of London is one of those areas that has been home to waves of forced migrations: Huguenots, Jews, Bangladeshis, Somalis; and (I’m risking a cliché) the streets are a palimpsest. Here is 19 Princelet Street. The synagogue in the building is no longer used as such. This is the museum of migration and diversity now. It tells the story of London’s immigrants through and for the experience of children, from the Huguenots to the Bosnians, Somalians, Sudanese, who have come here more latterly. Above it is a time-capsuled, caballa-strewn attic room with weaver-light windows and bowing floorboards. It was abandoned in 1969 by its reclusive resident, a story elegantly explored by Rachel Lichtenstein in Rodinsky’s Room.[1] But the building, like the life stories it contains, is frail, and visiting is by appointment.

Here is Brick Lane: the widely touted curry-mile that true Londoners steer clear of (“we” know that the Pakistani restaurants around the corner are far more “authentic”). Street photographers filter up their shots of the old shop sign for CH N. Katz, while restauranteurs try and lure you in with outrageous discounts.

Here is the Jamme Masjid, the area’s Friday mosque. It’s a Grade II* listed building.

Listing descriptions are diverse in themselves: some just two-line job-done signifiers of a thing to behold; enough for us to believe it is of value (like: “FOURNIER STREET Nos 1 and 3. Probably mid C18. A pair. Yellow brick, partly rebuilt with concrete lintels to some windows. Parapet and black pantiled roof. 4 storeys, 3 windows each. Shop fronts.”), while others have been updated, and now include the reasons for designation. The Brick Lane mosque for example:

Sequence of uses: a uniquely complex instance of the ‘recycling’ of a place of worship, its succession of religious uses encapsulating the rich migration history of East London.

The Brick Lane mosque list description is layered too:

BRICK LANE JAMME MASJID (former Neuve Eglise) (Formerly listed as: FOURNIER STREET E1 GREAT SYNAGOGUE) (Formerly listed as: BRICK LANE E1 GREAT SYNAGOGUE) (Formerly listed as: FOURNIER STREET BRICK LANE JAMME MASJID).

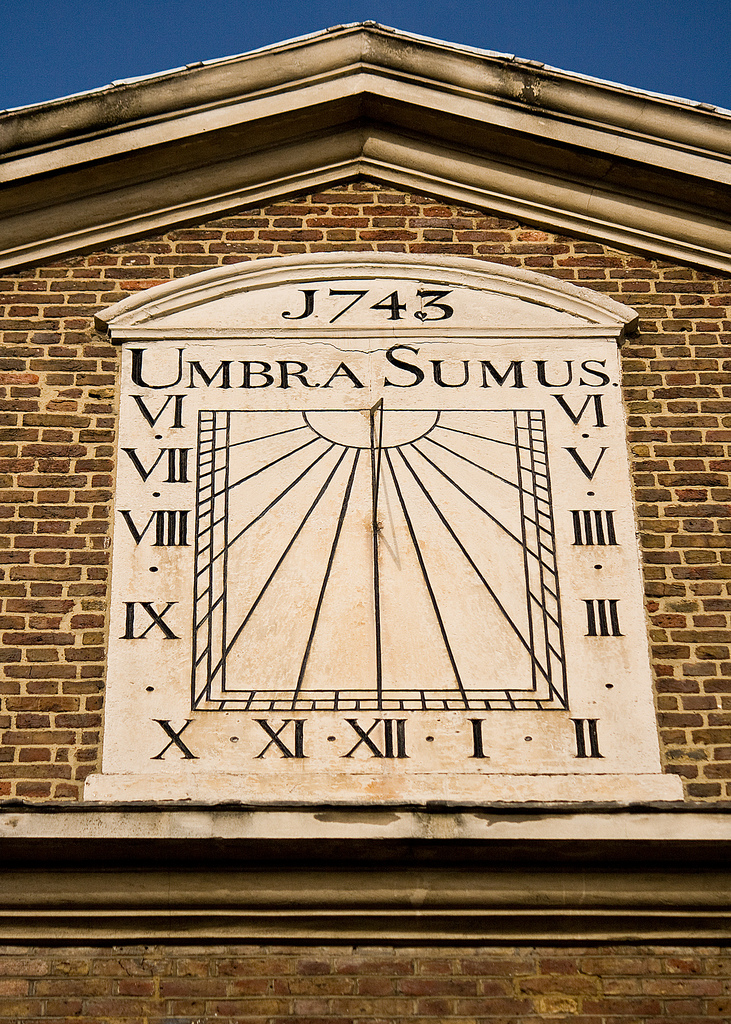

It’s a large, dark, brown-brick building (MATERIALS: Stock brick with stone plinth and dressings; Welsh slate roof). It’s two tall storeys, with an attic. Most of the buildings are two or three storeys around here, plus attics and basements, but the narrowness of the streets and the formalism of this building give it an austere dominance. All the windows are striking: plain glass but explicit in their religiosity. There’s a large Venetian window on the Brick Lane elevation, and a circular window in the pediment, like the sun. To Fournier Street, the windows are round-headed on the upper floor, suggesting that illumination again. The sunshine spread of the radial glazing bars contrast with the dark brick, but synthesize with the sundial in the triangular pediment above: “umbra sumus” it says. We are but shadow. The date is 1743.

From the Brick Lane Jamme Masjid list description: Sequence of uses: a uniquely complex instance of the ‘recycling’ of a place of worship, its succession of religious uses encapsulating the rich migration history of East London. This little patch of London is one of those areas that has been home to waves of forced migrations: Huguenots, Jews, Bangladeshis, Somalis; the streets are a palimpsest.

The Neuve Eglise was built to serve the Huguenots: French protestants who came to England after the revocation of the Edict of Nantes which halted their right to practice their religion. They were silk weavers; and the houses in Spitalfields have glazed attics, built to allow the light that they needed to work. Even this building has a glazed skylight, and Hebrew inscriptions survive within the corridor below it. Because after a stint as the headquarters of the Society of for Propagating Christianity (interested in the area’s Jewish immigration); and a period of Wesleyanism after 1819; the building became a synagogue. Orthodox Jews driven from Lithuania and the pogroms of the Russian Empire worshipped here. This was 1897, and that’s when the inscriptions date from: the upper story became a Torah school. But the East End is also a place that people move out of – my own grandparents did – and its only recently that it’s become a place to aspire to. Following Partition, Indians and Bangladeshis came to the area, while the Jewish population moved to the leafier suburbs. In 1976, the synagogue became a mosque. It was remodelled ten years later. In 2009, DGA Architects were commissioned to add the distinctive “minaret-like” feature described above.

There are principles for listing, set out by the Department for Culture, Media and Sport in 2010, and there’s supplementary guidance from Historic England. The key line in the DCMS guidance which supports the omission of the minaret from the listed building is this:

buildings of less than 30 years old are normally listed only if they are of outstanding quality and under threat.

It’s known as the thirty-years rule, and it exists to some extent, more or less rigorously defined and imposed, in the heritage practice of many countries. It presupposes that we can’t understand significance until the future: that the future of the building determines its past. Its significance now is more significant than its significance then.

I would have thought we knew the significance of the minaret. It’s there in the reasons for designation. The Brick Lane mosque – in all its layers – is the materializing of flow; the stabilizing of diversity; the implementation of rules in an unregulated life; making away into home through structural implementation. But in stating that we don’t know its significance we are slipping on “stubborn chunks”. At one level, there’s an acceptance that we’re beyond arbitrary cut-off dates, that more recent parts of a building that fit with historic use only increase its significance, and that heritage needs to represent the diversity of culture. At least we in the heritage industry have been saying so for years. And Historic England states on its website that understanding the heritage of faith and commemoration is an important aspect of Historic England’s work. Yet here, too recent to be of special interest is directly counter to the reasons for listing. In the menudo chowder of life, “some stubborn chunks are condemned merely to float,” Gomez-Peña says.[2] And although we claim that heritage has the soft power to contribute to culture, so frequently it hangs back.

Am I a Londoner? More than half my life has been spent in this city. I’m the great-granddaughter of a Hackney farrier; the great-great-great-granddaughter of a City of London alderman. I’m the granddaughter of a woman who fire-watched throughout World War II from the roof of Her Majesty’s Stationery Office and a man who was born within the sound of Bow Bells. But I wasn’t born here. So many of us weren’t. So few of us can trace ourselves back more than two generations in this city, such is its flow. But our heritage mechanisms privilege staying. The stationary. Movement can only be understood when it’s stopped.

So few of us can trace ourselves back more than two generations in this city, such is its flow. But our heritage mechanisms privilege staying. The stationary. Movement can only be understood when it’s stopped.

Could anything be more London than the Brick Lane mosque? More exemplary of the writing and re-writing of the world city in the world, worlding itself?[3] Can’t heritage have a bit more belief in that world? Be lured by its aliveness?[4] The minaret is architect-designed. It’s a striking, interesting, attractive thing: it will tick those future boxes to do with architectural and historic interest. I dare say it even has staying power. But couldn’t we say that even if it was run-of-the-mill from the bog-standard minaret pattern-book, the layer that it adds to the palimpsest is indicative of how diversity writes itself into the fabric of places; of how we make the vagaries and temporalities of a complicated world stick to place? Couldn’t we say that the value of diversity is now? Personally, I’d like to see a revision of the idea of listing, and in another blog post I will look at how Historic England is concretely democratizing the process, but for now, as someone who struggles to own being a Londoner, it’s worth noticing how acts of heritage creation knock diversity in heritage into a future-time, a sort of diversity double-speak that shouldn’t be inevitable. There is a power to heritage, and with power, as my grandfather undoubtedly would have said, comes responsibility.

https://historicengland.org.uk/listing/the-list/list-entry/1240697

All photographs courtesy of the photographers via flickr.com, and used under CC.BY.2.o or CC BY-NC-ND 2.0 licence. Many thanks for their generosity.

[1] Lichtenstein, Rachel. 1999. Rodinsky’s Room. Granta

[2] Quoted in Homi Bhabha’s The Location of Culture. p313

[3] Barad, Karen. 2007. Meeting the Universe Half Way. Duke University Press. p160

[4] Barad, Karen. 2012. “On Touching”. differences. 23(3): 207

There is a power to heritage, and with power, as my grandfather undoubtedly would have said, comes responsibility.