Sky Tip Circumstance

A new short film has been created by Heritage Futures Creative Fellow, Antony Lyons. This is the first of three in a series that have emerged from field investigations in the three ‘Transformation’ study areas. The work also forms part of the ‘Evening In Arkadia’ creative project and features a music soundtrack by Adrian Utley, guitarist/composer with the band, Portishead.

A geopoetic film. A meditation on time, attachment and change.

‘Evening In Arkadia’ is a creative landscape-based project operating across three landscapes undergoing transformation. It is supported by Heritage Futures/AHRC and Arts Council England.

It is currently being screened at Wheal Martyn, Cornwall, UK, as part of the temporary artist-residency ‘Limbo Landscape Lab’. Wheal Martyn is a partner in the Heritage Futures research programme.

The film can viewed online at https://vimeo.com/267828721

About the film:

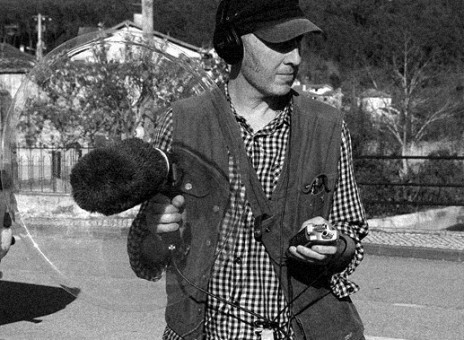

“This film is time-compressed. I recorded it hand-held for over 30 minutes, in the shelter of my trusty mobile studio/campervan. The circumstance was happenstance, serendipitous. The occasion arrived after many visits, over the course of a year, in the environs of the Sky Tip mound of mining waste outside St Austell in Cornwall – the centre of the long-established industry of kaolin mining. The Sky Tip has slowly, yet inexorably, inserted itself on my radar, and also now it is the focus for a project by a group of photography students – from Poltair School – with whom I’m working.”

Antony Lyons, www.antonylyons.net

“The piece provides a poetic and thoughtful mediation on time, duration, landscape, loss, change and transformation. Its evocation of legacies and engagement with the shifting values of waste and heritage illuminates key themes emerging from the Heritage Futures research programme, and in doing so, it touches on key social, cultural, ecological and political issues of the present moment. In its closely attentive yet hazy observation of a specific contested landscape feature, it invites us as viewers to similarly closely and quietly observe continuity and change, movement and stillness in the landscapes around us.”

Rodney Harrison, Professor of Heritage Studies (UCL) and Principal Investigator on the Heritage Futures programme.

SKY TIP

Sky Tip is waste.

Sky Tip is beloved, treasured.

Sky Tip is sand and mica.

Sky Tip is edgeland.

Sky Tip is heritage, iconic.

Sky Tip is solid, fluid.

Sky Tip is a playground.

Sky Tip is out of bounds.

‘THIS IS NOT A PLAY AREA’

Sky Tip is a symbol.

Sky Tip is a problem.

Sky Tip is waste.

Sky Tip is private.

Sky Tip is public, commons.

Sky Tip is dominating, 50m high.

Sky Tip is disappearing, eroding, crumbling.

Sky Tip is present.

Sky Tip is there.

It is not there.

Soundtrack collaborator, Adrian Utley on the process of production, and his encounter with the research situation:

“That’s very much what I liked about it – that it’s something that’s happening. I mean we like the Sky Tip, don’t we? I haven’t been with you to see it yet, but I have seen it in the past. And go down to Dartmoor, which I go to a lot. There’s a whole history from the Stone Age right up to now, you know? Clay mining… and then you see the tin mining and stuff. And actually it’s quite attractive. It’s part of the landscape. Because the landscape is claiming it back, and it makes it less raw. You could look at it and think ‘oh my god, this would have been teeming with people’ and you know, it’s in the middle of nowhere now. Water is very much part of the Dartmoor landscape really, as in loads of wild areas that I’ve been. And you see its action all over, how it wears everything, and the Dartmoor streams with rocks and the energy that they have. Things are always changing, massive boulders moving, and there’s a Tolman stone down there, which has got a circle cut out of it, which has just basically been worn away by the action of the river. And it’s huge! People go through it to cure rheumatism, and stuff. The Tolman stone.

For the soundtrack I had a couple of techniques that I wanted to use. It was a layer of sound, which went from beginning to end. And then I did an improvised layer of sound with a new technique that I’m developing now, with a guitar. And then I got them on my mixing desk and just blended between them, as it felt, you know. There are one and a half minute, two minute loops. So we took a section and made it repeat. And they overlap each other, so you don’t actually get the same thing happening over and over. But there is the same thing, but they’re offset from each other. There’s some clicking as well which is me treading on pedals. I kept that in. You get other resonances happening. Harmonics. From the thing. When you get these clusters of sound, there’s a whole world above it that doesn’t actually exist. You get it in minimalist music, like Steve Reich. Repetitive phrases that overlap. And then you start to hear a kind of other melody that isn’t actually there – that’s created through the harmonics of the others. But it’s about a feeling for a moment, and tomorrow that feeling might be different. Probably will be different. And if you were living in a hut next to it and made some music, it would be different again.”

But it’s about a feeling for a moment, and tomorrow that feeling might be different. Probably will be different.

Context:

Cornwall’s extraordinary clay mining landscape is a zone of rapid transformation, which will continue to evolve and change in the future. Human efforts combine with natural processes in sculpting and changing this unique landscape. Environmental artist Antony Lyons is the summer 2018 artist-in-residence at Wheal Martyn – the UK’s only museum which celebrates china clay mining – past and present, near St. Austell in Cornwall. Lyons is occupying an industrial heritage space at the museum, as an ‘open studio’. He is also working with musician Adrian Utley – the composer and guitarist for the band Portishead – to develop new video-sonic artworks for display at the museum over this summer and into the autumn.

Mid-Cornwall’s china clay country has seen many changes over the past several hundred years, and it continues to change in dramatic ways. Mining has left enormous artificial hills, once known as the Cornish Alps, in the area near St Austell. Leading up to the culmination of the art project, in October, there will be presentation of films, sculptural installations and printworks designed to prompt reflection on change, impermanence and potential futures. The project raises questions about decay and decline, as well as regrowth and renewal.

The Bristol-based artist has already spent two years exploring and researching in Mid-Cornwall, and is collaborating with Heritage Futures academics at the University of Exeter and members of the China Clay History Society in carrying out his creative research.

One of the features of interest is the “Sky Tip”, a pyramid-like, 50m-high artificial mountain of mining waste material north of St Austell. The Sky Tip, a relic of the industrial past, will soon become the centrepiece of a new Garden Village development.

The effect of the Sky Tip is partly due to its strong visual presence – its distinctive outline being clearly visible on the horizon when viewed from high ground over 20 miles away. Beyond the dominating presence and the part it plays in forming the local landscape character, there are the strong personal attachments it evokes. For some it is a marker of a lifetime of work ‘winning the clay’; for others a symbol of proud Cornish identity to be emphasised by flying the flag with the white cross of St Pirian at the summit; and for many young people of St Austell, it is a place of freedom, an in-between zone, a wild space of escape.

For me, it also carries echoes of another huge artificial mound of rubble in southern England, namely the neolithic Silbury Hill near Avebury in Wiltshire – separated by hundreds of miles and by thousands of years. Silbury is more rounded now, but it’s dimensions are very similar, and – as in the case of the Sky Tip – the ‘positive’ form of the mound is partnered by the ‘negative’ void of the pit. At Silbury, this void space is a sculpted depression, water-filled in winter, that has been speculated by some to form a vast pregnant female shape. The flooded pit next to the Sky Tip can likewise be a site of speculation and fantasy. Aerial photos reveal a cross-shaped earthwork in the lake, somewhat reminiscent of the famous land-art earthwork ‘Spiral Jetty’ by Robert Smithson in the salt-lake of far off Utah. Could the inspiration for the water-framed earthwork here at the Sky Tip be a reference to the symbolic cross often flying at the summit?

Coming back to the film, where the rolling mist is a fortuitous echo of a film I made in another in-between, limbo landscape. This was filmed, also for 30 minutes, on the Suffolk coast, and features the now defunct Orford Ness lighthouse appearing out of the mist, and then fading back into the white-out oblivion – a metaphorical ending that resonates with the destiny of the lighthouse. The coast here is shifting, receding, and the Orford Ness lighthouse will be removed by erosion and wave action within a few years.

More recently – in the third landscape involved in this creative project (Evening In Arkadia/Heritage Futures), storm-cloud conditions provided an opportunity to similarly film the Côa Valley in Portugal. Not threatened with erosion or oblivion just yet, it was however facing inundation by the large Foz Côa dam project in the 1990s. The reservoir would have drowned the extensive and hugely impressive prehistoric rock-art engravings found in the valley bottom. The protests to save the valley and its precious archaeology were successful, and now it is a place where both ancient animal life (as represented in the rock-art) and contemporary wildlife (enhanced by a growing ‘rewilding’ project) are celebrated. While out filming, my desire to capture the misty valley conditions for a full 30 minutes was however cut short by the increasing vigour and intensity of the storm, accompanied by torrential rain and lightning – a reminder of the elemental watery forces that will endlessly form and reform these landscapes over the course of deep-time.”