Storii

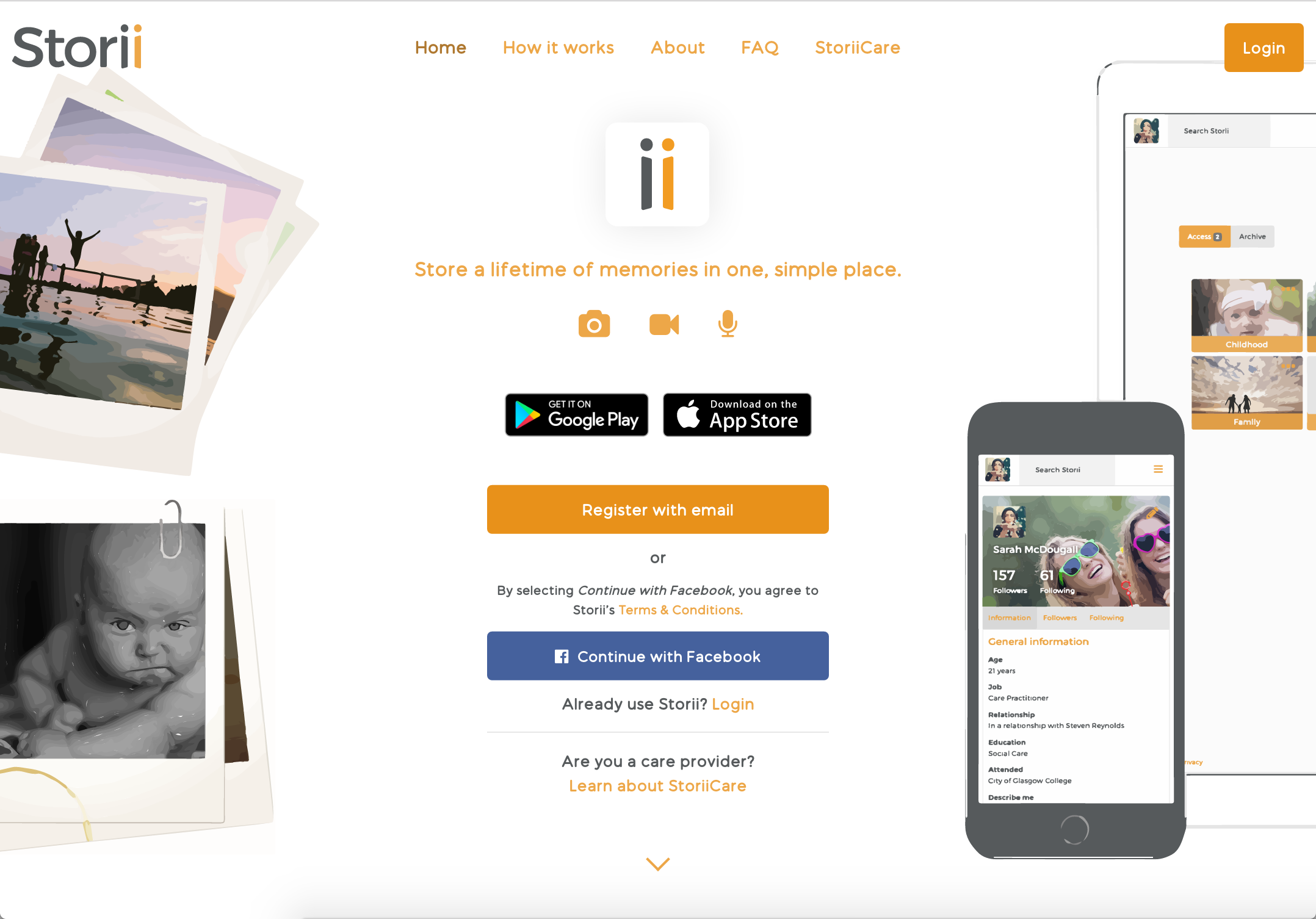

As part of the Profusion theme research we are looking at professional and semi-professional services offered to cope with domestic profusion. This includes the work of declutterers. Recently, we extended this to a new area: the digital. I met with Cameron Graham (Founder and CEO) to talk about Storii; a web and app platform designed (as the website explains) for people to ‘store and organise their life moments’ using cloud-technology. By providing unlimited storage, and an interface designed to facilitate interaction, users are invited to ‘store a lifetime of memories’ by uploading digital content including photographs, videos, audio-files, and weblinks. As Cameron told me: ‘it is important to preserve this properly, as it is so easily lost’.

Across the domains we research in (homes and museums) digital content, and the ‘memories’ and ‘stories’ made manifest through this content, is certainly perceived at risk of being easily lost; both through technological obsolescence and content overload. The former is illustrated particularly vividly in this newspaper article about the struggles of preserving a life’s work stored on floppy disks, tape cassettes, CD-roms, and computers ‘vulnerable to decay and disintegration, [as] leftovers from the unrelenting tide of technological advancement’. Householders recount their challenges of storing, but especially of identifying and finding, treasured materials from amongst vast quantities of accumulated digital stuff stored on computers, hard-drives, cameras, mobile phones, social media sites, and other devices.

By providing unlimited storage, and an interface designed to facilitate interaction, users are invited to ‘store a lifetime of memories’ by uploading digital content including photographs, videos, audio-files, and weblinks. As Cameron told me: ‘it is important to preserve this properly, as it is so easily lost’.

Recognising such challenges, Cameron described how Storii is designed around the principles of having everything stored in one secure place, and organising content or ‘keeping everything tidy’. He pointed out how the app uses interface ‘breadcrumbs’ so that users can easily navigate and find content ordered into either ‘uncategorised’ or ‘customised’ folders, and that because it has no ‘auto upload button’ users must manually decide what to import. Selection is not driven by space-constraints (storage is not limited) but encouraging users to log the meaningful or significant; or what Cameron spoke about as being content with associations to ‘the moments that really matter’ or is ‘of importance to the person’.

Cameron described Storii as being a ‘personal museum’. Through the app’s design to store, order, preserve, and share digital content, I would agree that Storii demonstrates (what Susan Crane (2000) calls) a ‘museal consciousness’. Yet, while recognising similarities, it is important to consider how a digital form of museal consciousness might be different from – and indeed help to reveal some of the assumptions underpinning – more traditional and non-digital museum sites. For example, Storii (like the homes we research in) holds potential to become a repository for values that people ascribe to content that may diverge from those that typically characterise heritage management and conservation.

Selection is not driven by space-constraints (storage is not limited) but encouraging users to log the meaningful or significant; or what Cameron spoke about as being content with associations to ‘the moments that really matter’ or is ‘of importance to the person’.

One key difference between Storii and the museums we research in is that the app does not attempt to define any criteria for what is logged (or for identifying ‘the moments that matter’). Doing so seems rather less the point than simply encouraging users to develop a sensibility towards discriminating; or requiring them, by not having an ‘import all’ option, to make an active decision about what and what not to log. This is perhaps surprising given that there is little practical need for users to do so. Storage, as noted earlier, is unlimited. This begs the question of why users are encouraged to make active choices about which content to import, given there is little practical necessity for them to do so?

Here I move away from my conversation with Cameron (we did not discuss this) to look to popular and academic commentary. According to some commentators, it is precisely this sensibility or responsiveness towards being able to discriminate (or what might be thought of as kind of ‘filtering’) that is increasingly at stake in the digital age. This is summed up in a perspective that, as a New York Times article once claimed, ‘the web means the end of forgetting’ because the internet ‘records everything and forgets nothing’. Faced with the possibility of perfect memory through unlimited digi-information recall, Mayer-Schönberger (2009: 15) argues that it is crucially important we ‘remember how to forget’. Too much recall, or holding onto too many details, can hinder our ability for abstract thought and decision-making. The important point made in this book is that forgetting is bound up in our individual and collective ability to make judgements and ultimately to recognise (to return to Cameron’s words) ‘what matters’.

By comparing Storii to the museum sites we research in, crucial questions that need further sustained reflection are raised. Here, the question of what (precisely) forgetting or letting go does? To do so requires moving beyond framing debate about letting go predominantly in terms of practical necessity or resource constraint to think deeply about what practical, social, and cognitive effects forgetting has for museums. And, more crucially perhaps, to reflect on what kinds of socio-cultural work it enables them to do.

Crane, Susan A., 2000. Introduction: Of Museums and Memory. In: S.A.Crane (ed.), Museums and Memory. Stanford: Stanford University Press, pp.1-13.

Mayer-Schönberger, Viktor, 2009. Delete: The Virtue of Forgetting in the Digital Age. Princeton: Princeton University Press.