Torbay’s Hidden Treasures

This dispatch is the first from an ongoing collaboration between creative practitioner Shelley Castle (Encounters Arts) and researcher Jennie Morgan. Together they are working on the Profusion-theme of Heritage Futures. Over the Summer of 2017, Shelley and Jennie invited householders to show them objects they would like to keep for the future. Shelley also installed Story in the Object at Torre Abbey. They will continue to update on their collaboration.

Torbay was once a very wealthy area: a playground for rich Victorians in search of a sunny seaside resort. There are still promenades with souvenir shops, theatres with popular shows, and miniature red trains ferrying tourists around the sights. With the sea as a backdrop, second hand shops strain at the seams like they probably do all over the country, and souvenir shops burst with mementos made in China. It is a place of particular profusion matched with particular scarcity.

It is a place of particular profusion matched with particular scarcity

Over several weeks of working on the ground in this place, we have uncovered an eclectic mix of items that people want to keep for the future. The length of ‘futures’ thought about are often different, ranging from post human to within a lifetime or generation or two. And the objects shown to us are as different as the people and the stories that accompanied them. Yet it is striking that the majority of those we have met spent a good deal of time thinking very carefully about what to select. Amongst the objects were a disheveled rag doll, a collection of papier-mâché figures, a radio, a key, a concertina, and a circus programme.

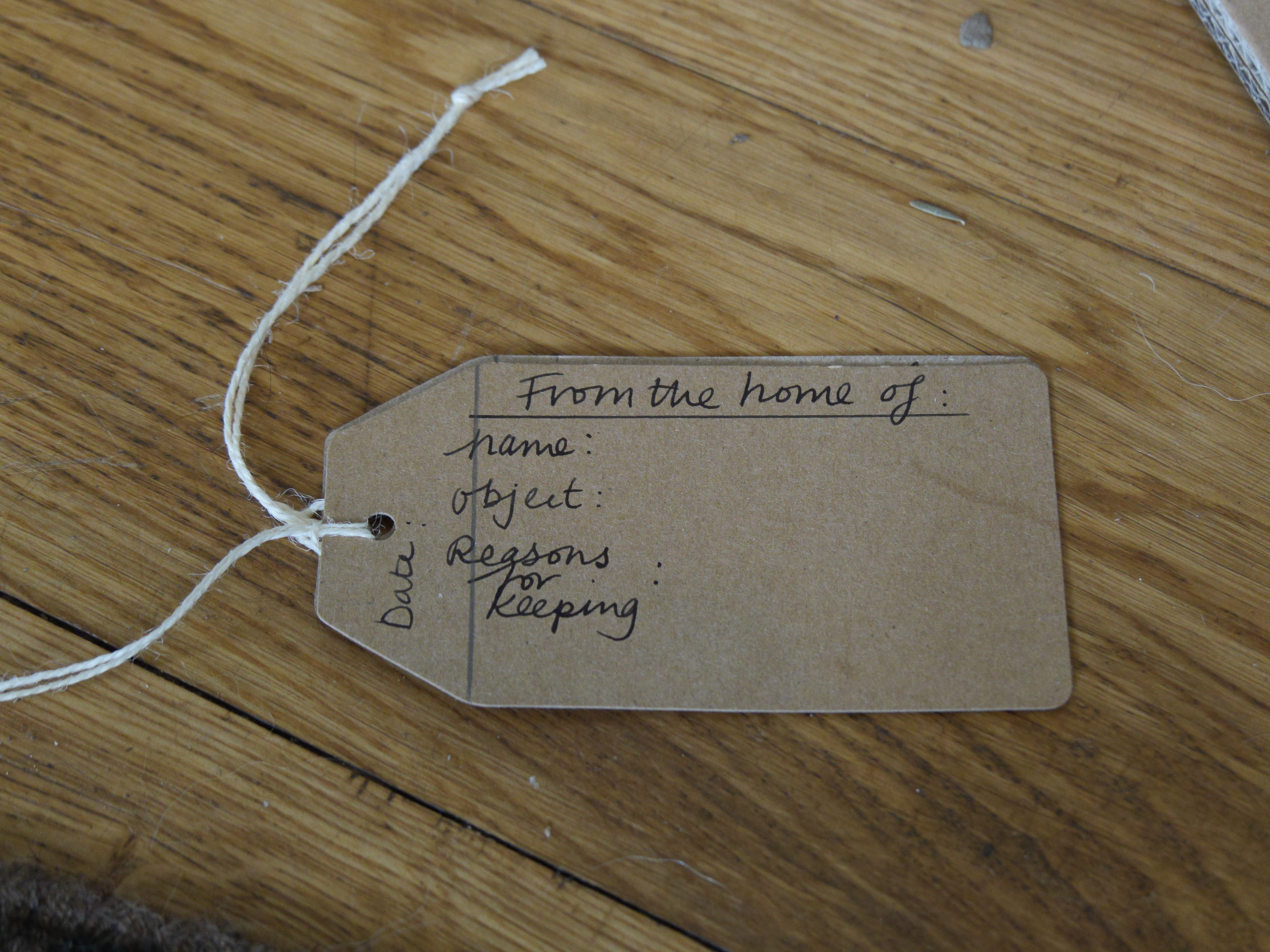

What usually (although not always) united their choices was that the objects resonated a highly personal charge for the owner. This seemed to be passed on during the telling of their story, making the objects important to us too. It’s something we would like to dig into as our collaboration continues. Does a story, especially an emotionally charged one, tie people together, objects to people, creating links that act as a glue? What is the object without a story? Some people felt it important to make a record of the story to sit with the object so that future owners (often children) would understand its potency. One person described how they had lodged a handwritten note inside a treasured clock explaining why it was important to them. They hoped this would stop the story from being lost in the future. Perhaps indicating the effectiveness of this technique, we were unable to read the note because it could not easily be retrieved. Others told stories that meandered around and through the object as if it were a vessel for particular hopes, memories or dreams for the future.

Sometimes the stories that connect people and objects emerged in unexpected ways. During a visit to Mary we felt privileged to be read a poem she had written about her Dad: ‘the collector’. Over a lifetime he had acquired treasured ‘trinkets’ and ‘bric-a-brac’. Her wonderful poem told us about accumulation; the investments made (of personalities, time, money, connections, and emotion) into things; and the intertwining of loss, care, and the ‘rehoming’ of material legacies. You can watch the clip below, or here.

What is the object without a story?

For both of us, working on Profusion is having an increasingly powerful effect on our own connections not only with ‘things’ but with digital information. Shelley has found herself questioning very deeply what she has attachments to and if these attachments are helpful or not. The result is that since working on the project she has already sold five glass domes (kept for a decade in case she ever made something that fitted them), a beautiful black cabinet (kept for twenty years because she didn’t want to lose money on it even though it never really fitted in the house) and her laptop hard-drive is looking sparse. Jennie has caught herself borrowing strategies for dealing with her own household clutter. For example, using the decluttering tip of treating a sort-out at home like ‘going on a holiday’ and needing to ‘know the destination’ to decide what and what not to hang onto.

Identifying what really matters may help to more easily get rid of stuff that is no longer needed. It can reduce what (some people told us) has the potential to become problematic profusion. Yet we have also learnt that not everything is so easily removed. One person who was divesting himself of stuff talked about how his father’s shirts had been ‘trapped’ at the back of his own wardrobe for twenty years. He was now unable to throw them out because the longer they were there the more ‘stuck’ they became.

Yet to make more sustainable futures there is rationale for considering more carefully what we bring into our homes, and how we dispose or get rid of material we no longer want. A very good starting point is to investigate what we really do want to keep for the future.

Shelley Castle, Jennie Morgan

We have also learnt that not everything is so easily removed