Towards Nuclear Cultural Studies

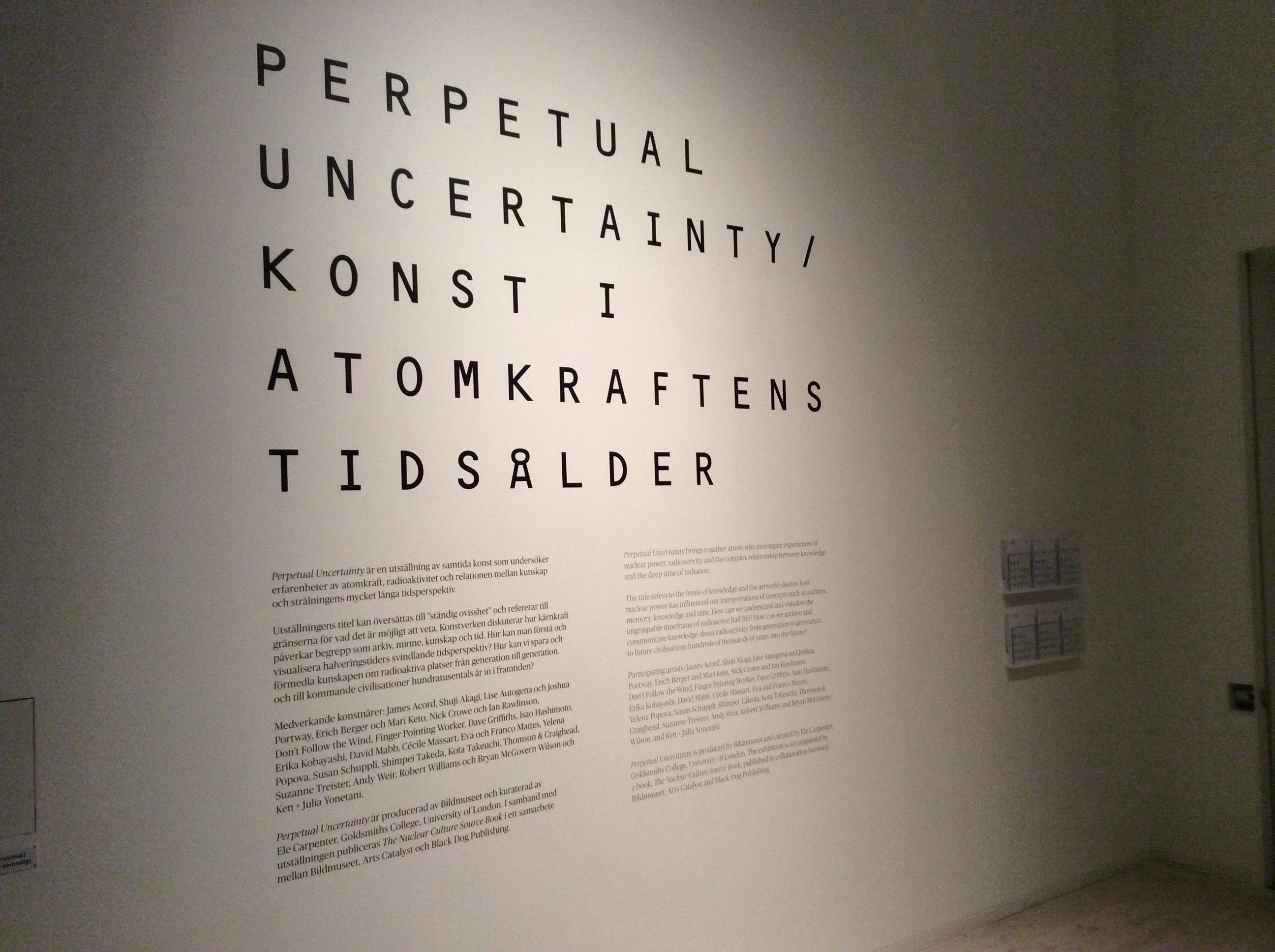

The exhibition Perpetual Uncertainty / Contemporary Art in the Nuclear Anthropocene at Bildmuseet in Umeå, Sweden (2 October 2016 – 16 April 2017), brings together artists from Europe, Japan, the USA and Australia to investigate experiences of nuclear technology, radiation and the complex relationship between knowledge and deep time. Curator Ele Carpenter, who also edited the comprehensive accompanying Nuclear Culture Sourcebook (Black Dog, 2016), defines the topic of the exhibition in the following way:

“The artworks explore how nuclear weapons and nuclear power has influenced our interpretation of concepts such as archives, memory, knowledge and time. How can we understand and visualise the ungraspable timeframe of radioactive half-life? How can we archive and communicate knowledge about radioactivity from generation to generation, hundreds of thousands of years into the future?”

Indeed, many interesting interventions are made about such issues by the many artworks that stretch over four floors of the museum. I will briefly discuss three of them that each seem particularly interesting in the context of our current research on heritage futures.

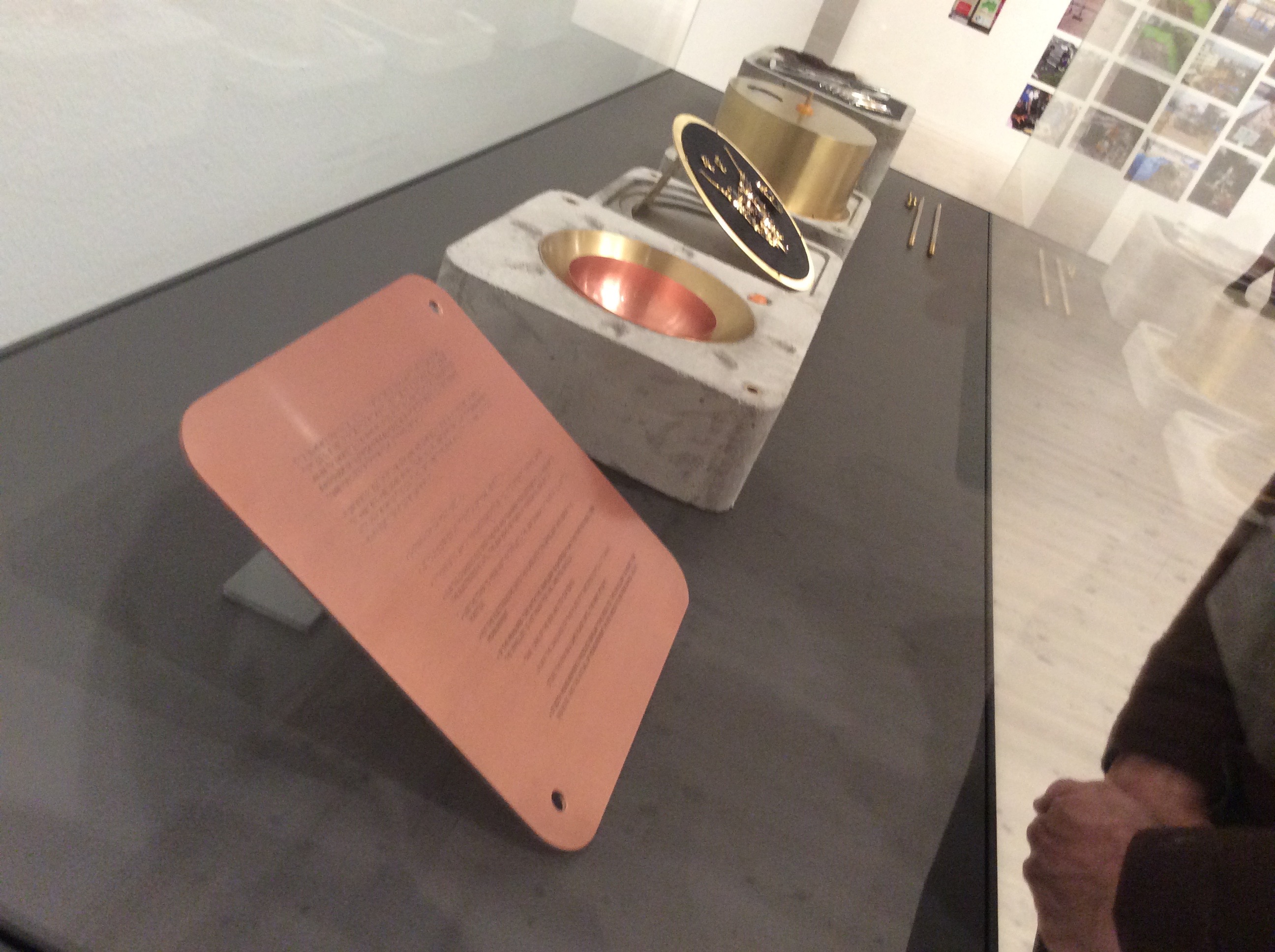

Erich Berger and Mari Keto’s installation entitled Inheritance consists of a box and a ritual to be continued into the future. The box is passed on as an heirloom from one generation to the next and contains, among other things, jewellery made of various precious materials including radioactive stones. The jewellery can be used outside the box as soon as the accompanying radiograph indicates, through a ritualised test, that the stones are not significantly more radioactive any more than natural background radioactivity. Inheritance is effectively not a set of things on display but a process to be executed in a future-making practice. The work consists of a bunch of lifeless objects but it is at the same time very human as it involves human rituals, human values, and human ornaments; Inheritance evokes the distant future but also many presents and even future pasts; what is more, the natural world, science, technology and human rituals and behaviour are almost seamlessly connected with each other. This is a future of anticipated risk but also a future of continuous appreciation and continuing change. Maybe the instructions given by the artists could be applied in other future-making practices too:

Take care of the box and its contents – update the language of this plate if it becomes difficult to read – store the box in a safe place until the next attempt.

Dave Griffith’s Deep Field [UnclearZine] consists of a microfiche and microfiche reader. This archaic medium is used to convey reliably for up to 500 years into the future a message to coming generations about Belgian nuclear waste repositories. That message differs significantly from a sober factual record of nuclear waste. Griffith records conversations, poetry, drawings and pictures that have a colloquial and even folkloristic character. He also includes references to Belgian nuclear workers playing golf after work. The intention is to complicate matters for future generations accessing this record. Pasts, presents and futures are not simple and straightforward but complex. Who is to say that seemingly sub-cultural processes and events in the present will not be significant in the far future in order to make sense of what lies beneath? This work raises the intriguing question of what kind of record may be most interesting and revealing in the future about the nuclear waste we leave behind in the present. Another question posed is about appropriate media and genres in long-term communication. Is there a message in the cumbersome and often frustrating experience of reading a microfiche? Are poetry, myth and folklore legitimate ways of engaging with future generations when the matter is radioactive? Should we communicate with the future in simple or in complex ways? Griffith favours complexity, whereas Berger and Keto appear to favour something more palpable.

![Dave Griffith's 'Deep Field' [UnclearZine]](https://heritage-futures.org/app/uploads/2016/11/Nuclear-Cultural-Studies-3.jpg)

Robert Williams and Bryan McGovern Wilson’s work Cumbrian Alchemy was first shown in 2013. It fills an entire room and consists of photographs, drawings and a wooden cabinet filled with a variety of objects and documents linked to the Lake District which is not far from the Sellafield nuclear facility. Williams and McGovern Wilson place the questions that surround a planned final repository of nuclear waste into a context of folklore, prehistoric monuments, archaeology, geology, landscape, tourism and popular culture such as a Captain Atom comic book. Although Cumbrian Alchemy raises a number of big issues about continuity, order and knowledge, the folkloristic flavour displays considerable playfulness and is rather different from the complexities of Deep Field. Williams and McGovern Wilson’s work effectively culturalises nuclear waste in the region of North Lancashire and Cumbria, thus paving the way for our own investigations of alternative futures negotiated in the Lake District. Their language is material, much as inheritance, but the future is not processual and rather abstract and conceptual.

All the works in the exhibition ultimately phrase nuclear questions in a cultural way. In this sense, the emerging field of Nuclear Culture responds to the fact that “[s]ince the splitting of the atom, nuclear knowledge and experience have change the way in which we see and understand the world”, as Ele Carpenter mentions in the introduction to the anthology I mentioned earlier. But might we ask also to what extend the ways in which we see and understand the world has changed nuclear knowledge and experience?

It strikes me that nuclear technology is strongly naturalised here – in a similar way in which current discussions of the Anthropocene tend to be naturalized (Malm and Hornborg 2014). Most works in the exhibition employ nuclear references in order to comment in some way on the future of humanity, or a part of it, on planet Earth. Throughout the exhibition, applied nuclear physics and nuclear technology tend to be serious things that need to be understood regarding their profound implications and impact, not things that need to be investigated and questioned as cultural and social phenomena in their own right. But the future is made through practice, and practices are informed by perceptions of the future. That holds not only for artistic and heritage futures but even for nuclear futures. These things can be studied, and many in the Arts and Humanities would know how to do that. Uncertainties regarding practices and perceptions don’t need to be perpetual.

I end with a proposal. Let’s develop the interest in Nuclear Cultures further into a Nuclear Cultural Studies which applies the entire repertoire of approaches and concerns of Cultural Studies to the nuclear realm. To start with, we will need to think in terms of many nuclear cultures rather than just one. We should ask, whose voices are heard in specific nuclear cultures and who benefits from their practices? We should explore to what extent nuclear cultures are ideological, contested, multivocal, post-colonial, or gendered! We should be ready to compare and contrast hegemonic and subaltern nuclear cultures. In this spirit, I am very much looking forward to a continuation of the discussions about nuclear culture(s) that Ele Carpenter and the many artists involved in her ambitious and challenging project currently provoke in Umeå.

Cornelius Holtorf

Reference