If the Tunnel Tree Falls in the Forest

Many of us have heard the philosophical thought experiment that poses ‘if a tree falls in a forest and no one is around to hear it, does it make a sound?’ The question generates heated debates around the idea of sound, the loss of nature, humanity’s relationship towards nature, humanity’s self-importance, and whether reality is nothing more than humanity’s subjective interpretation of it. I also remember the song ‘If a Tree Falls’ by Bruce Cockburn in the 1980s that drew attention to the destruction of the Amazon rainforest, the displacement of native populations, the role of corporations, and the impact of climate change.

If we apply the thought experiment to the Pioneer Cabin Tree (also known as the Tunnel Tree), then we can safely say that when it toppled on 8 January, it made a sound that reverberated around world.

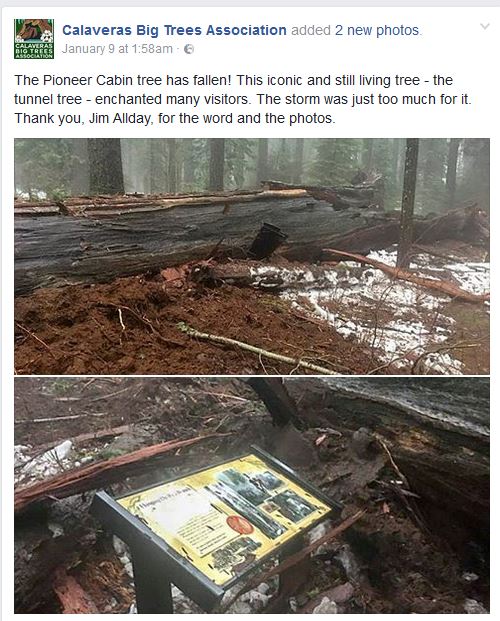

The Tunnel Tree is an old sequoia tree measuring 150 feet tall that has a hole carved in it (see Figure 1). It is located in Calaveras Big Trees State Park in Arnold, California. What sparked the news stories was the Facebook post by the Calaveras Big Tree Association:

‘Would it be horrible to suggest selling parts of it (sealed/varnished items from keychains, sculptures, tables, etc.) to benefit the park?’

I first read the story on the BBC website. The source of the story as it was told is important here as the BBC relayed it in a particular way. It first mentions the toppling, how old the tree was, its popularity among tourists, and culprits of the tree’s demise: the unusually severe storms hitting California and Nevada, and the fact it had a giant hole cut through it. Since the story originated from a Facebook post, the BBC article then highlights some of the social media comments that were generated. This, for me, sparked further investigation into how other media sites reported the story, and also how the social media comments revealed aspects of heritage that demonstrate our attachment to both nature and culture.

‘Ancient’ Trees Have Value

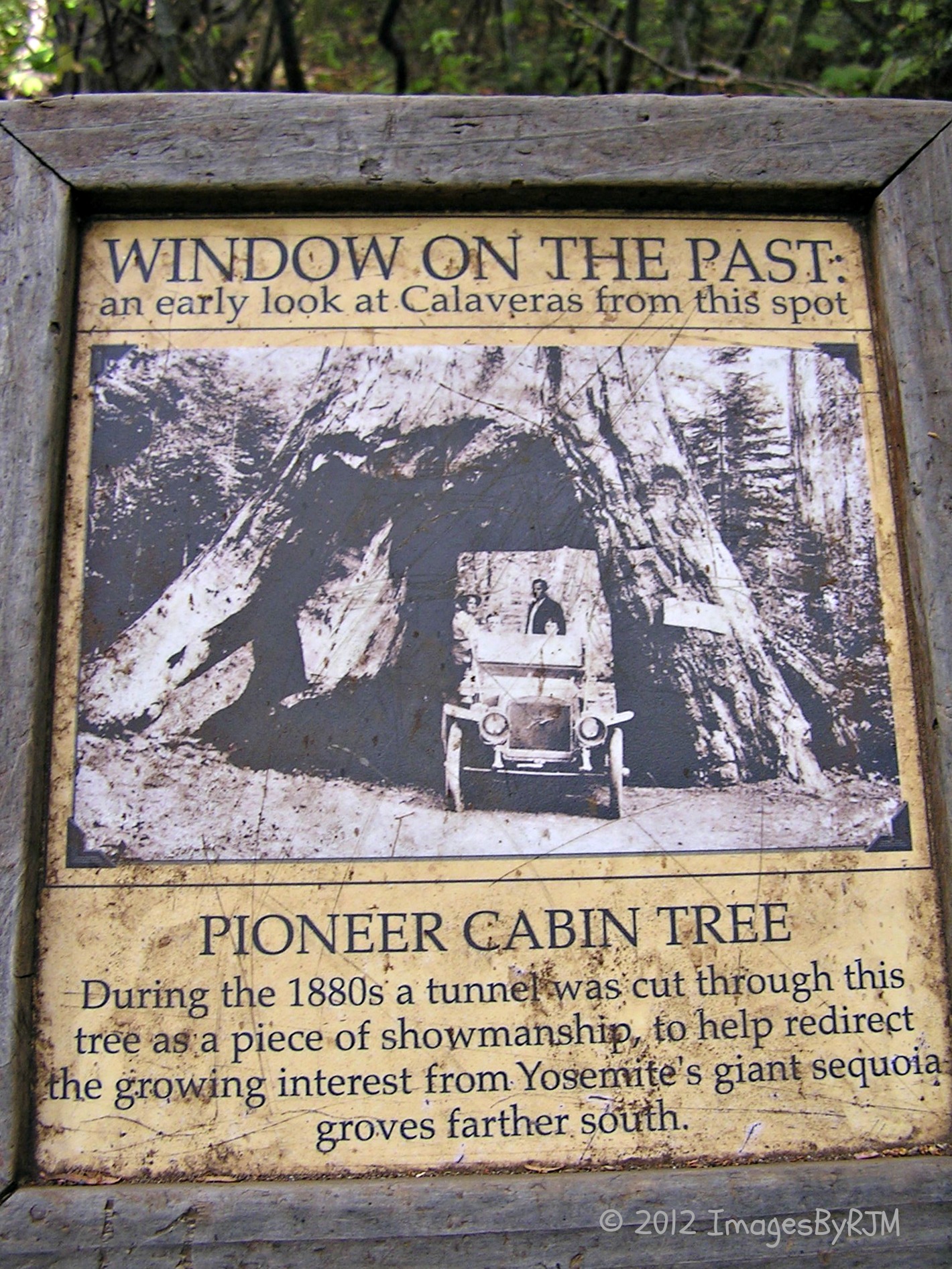

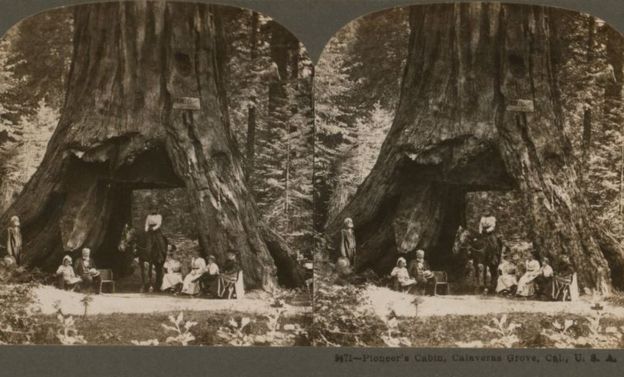

As the BBC mentioned, giant sequoias are related to the redwood – the tallest tree species on earth – and only grow naturally in California’s Sierra Nevada Mountain Range. The Forest Service says that there are just a few tunneled-through sequoias in California, with the remaining ones dead or in logs on their side. This makes this particular tree doubly unique. The Tunnel Tree was reportedly more than 1,000 years old (redwoods can live more than 3,000 years). As Baudrillard (1968) argues, there is something to be said about what is deemed old – especially when it is perceived ‘ancient’. While he was referring to objects, one could transpose it to the more-than-human, and suggest that in this case, any tree that is deemed ‘old’ will be considered worthy of preservation as it is a testimony of time. Clearly, trees have more value than simply their age due to their role, for instance, in the carbon cycle. And the National Park Service knows this when it commented in the NPR story that “Tunnel trees had their time and place in the early history of our national parks. But today sequoias which are standing healthy and whole are worth far more.” Yet my point is that there is something to be said about the age of the Tunnel Tree here: it is not ‘just’ a tree, but an old one, a living one and a unique one. Hence why it was seen as part of the Park’s heritage (see Figure 3).

‘The tree should be left to lay where it falls and it will likely sprout new shoots, which will grow into new giants.’

The Blame Game Part 1: Nature Did It

When the news stories came out, the headlines kept referring to the sequoia as a victim: they all referred to the tree being brought down by the storm. While this is true, it does point the finger at nature. In other words, had the storm not been there or so strong, the Tunnel Tree would still be standing. The BBC story indicates that these are the strongest storms to have hit the area in decades which was part of a seasonal weather system known as the Pineapple Express – ‘not to be confused with the Seth Rogen movie’, it clarified – but rather “an ‘atmospheric river’ that extends across the Pacific from Hawaii to the US West Coast, meteorologists say.” So, basically, we can blame nature for destroying itself and taking away our heritage.

The Blame Game Part 2: Humans Did It

Or can we? We find out that in fact, the tunnel that cuts through the tree was done by landowners 137 years ago (see Figure 4). NPR reports that “Tunnel trees were created in the 19th century to promote parks and inspire tourism”, as is also indicative of the sign featured in Figure 3.

‘At least it can now be replaced with a virtual tree with today’s technology.’

Almost 3,000 people posted comments on the Calaveras Big Tree Association Facebook page. This in itself is remarkable for a tree, demonstrating how social media can (to use Latour’s words) ‘reassemble the social’. Here, the tree becomes a catalyst (or, to use Latour’s words again, an ‘actor’) in gathering something akin to what Appadurai (2010) calls a ‘community of sentiment’. Since the tree can’t speak for itself, some did it for it, in defense of the tree – and turning on their own species, pointing out that humans are to blame for killing the tree in the first place. Here are just some of the posts:

- ‘you can’t cut a hole into a tree and expect it to live’

- ‘the hole always bothered me so much’

- ‘The tree was barely alive. Only one branch near the top with green. When it fell it shattered. No doubt damage from the tunneling made it brittle.’

It’s Human Nature

In a recent review in Nature, Richard Fortey describes Wohlleben’s The Hidden Life of Trees (Greystone: 2016) as a compelling book, yet “the anthropomorphism … is more spice than it needs.” He adds that “Trees are splendid and interesting enough in their own right without being saddled with a panoply of emotions.” However, when considering heritage, is it possible to see nature simply as ‘itself’ without anthropomorphizing it? Take for instance what the Calaveras Big Tree Association wrote on their Facebook post: ‘The storm was just too much for it’, and ‘it enchanted many visitors’. One of the Park volunteers wrote ‘We lost an old friend today’. Indeed, the ‘death’ of the Tunnel Tree is mourning the loss of life, as these posts attest to:

- ‘many memories created under tree, they will remain good memories’

- ‘a piece of my childhood is gone’

As a consequence, many posts suggest that measures should be taken to preserve the Tunnel Tree – or the memory of it. Here are some excerpts:

- ‘Would it be horrible to suggest selling parts of it (sealed/varnished items from keychains, sculptures, tables, etc.) to benefit the park? I love woodwork, and I think it would be a good way to preserve it still. Possibly keep a slab of it (to show the size of it), so people could see it who didn’t get the chance before this? I think it would be amazing if you could see and count the rings from all the years. I also think money could go to benefit the park (plant more trees, help support other large trees, fix damages, etc.).’

- ‘The tree should be left to lay where it falls and it will likely sprout new shoots, which will grow into new giants. Maybe 2000 years from now, when the shoots are mature, they wont cut a hole through it.’

- ‘At least it can now be replaced with a virtual tree with today’s technology.’

- ‘Separate the tunnel portion from the rest of the trunk, put it back in place securely so many more generations can share the experience & realize how ancient and massive they are. Then Mill the rest of it and build a “Redwood Forest Environmental Learning Center Treehouse ” over top , but not supported by the tunnel portion! This way it all stays in one place and it promotes preservation!’

- ‘As sad as this is, it does present an opportunity to use the timber from this tree for special projects, Guitar tops come to mind :-). It can be used, and its story could live on through music.’

What is striking to me is how remarkably thoughtful and original some of the suggestions are. Yet in all of these suggestions, the word ‘legacy’ comes to mind, and the notion that the tree should somehow last for generations to come, and also for people now – at least those who did not have a chance to ‘experience’ the tree in their lifetime, while it was standing.

It’s Nature’s Nature

Let’s say we take humans out of the equation. Would the Tunnel Tree have survived? According to Travis Andrew of the Washington Post, we find out that left to their own devices, “These trees are made to burn, their protective bark healing itself over time.” He adds the following:

“As written in a guide to the Calaveras Big Trees State Park, ‘Sierra redwoods evolved in the presence of fire, and not only have adapted to it, but depend on it in several ways. Heat from fire causes the cones to open and release the seeds. Fire clears the ground of duff, litter, and brush so the tiny seeds can reach the mineral soil and receive plenty of sunshine . . . The opening [in the Pioneer Cabin tree] has reduced the ability of the tree to resist fire. A few branches bearing green foliage tell us that this tree is still managing to survive.’”

All That Remains Is Change

But the Tunnel Tree gained notoriety and appreciation primarily because it was tunneled. As Travis Andrews suggests, one of the reasons for the tree falling is the very thing that attracted visitors to it in the first place. Try as we might, it is virtually impossible to separate nature and culture, humans and more-than-humans. Our relationship with the natural environment remains tense, fruitful and fragile. Yet through this ambivalence and tension, it is an ongoing relationship, nonetheless. Perhaps one thing that remains can be summed up in this Facebook post: ‘Poor tree. I’ve been there many times. Just goes to show you, everything changes.’

Academic References

Appadurai, A. (2010) How Histories Make Geographies: Circulation and Context in a Global Perspective. Transcultural Studies 1: 4-13.

Baudrillard, J. (1968/2007) Le système des objets [The System of Objects]. Paris: Gallimard.

Latour, B. (2007) Reassembling the social: An introduction to actor-network-theory. Oxford University Press.

‘Poor tree. I’ve been there many times. Just goes to show you, everything changes.’