Waiting for the Big One

Heritage has a long relationship with volcanoes, but does that leave us 'waiting for the big one' when it comes to the future?

#OnThisDay in 1980, M5.1 #EQ shakes Mount St. Helens. The northern flank of the volcano slides away in massive landslide (largest in recorded history), followed by a lateral blast traveling 300 mph. Forest within 6+ miles of the blast is leveled https://t.co/Yr8Iwln3pc pic.twitter.com/jRmSHec4W2

— USGS (@USGS) May 18, 2018

Today is the anniversary of the eruption of Mount St Helen’s in 1980, a massive eruption that devastated an area 600km2 and in which 57 people were killed. At the age of 15 it was the first volcanic eruption that I was aware ofand it formed the image of eruptions for me – rare, violent, changing whole landscapes in the blink of an eye. Volcanologists had been monitoring the volcano since early March when earthquakes and small eruptions began. This image of a hovering threat that will literally explode and change everything is a common image of eruption and is evident in international coverage of the ongoing eruption at Kilauea in Hawaii.

Hawaii volcano eruption update: Will Kilauea erupt TODAY? What does a red warning mean? https://t.co/cMFSvk7Rgz pic.twitter.com/wl08N9Zszr

— Daily Express (@Daily_Express) May 16, 2018

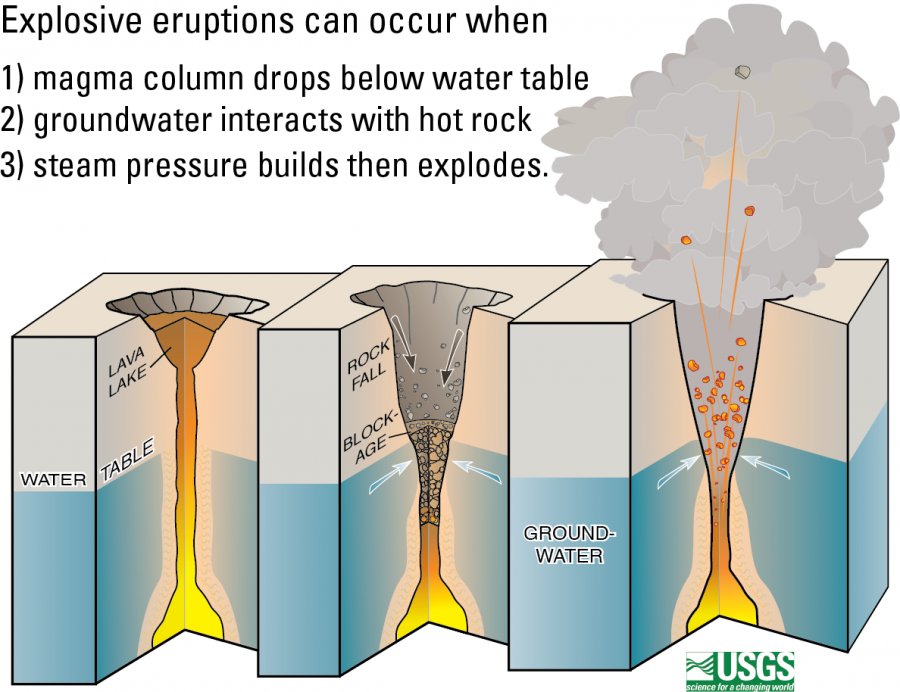

But this is not how most eruptions occur, and certainly not how Hawaiian eruptions occur. Kilaeua is a shield volcano which has been erupting near constantly for many years. Recently, the eastern rift zone, which has a number of small communities living on it has become more active, and this associated with a drop in the level of the lava in the two craters near the summit of the volcano. This drop in lava feeds the new fissures in the eastern rift zone, which is disruptive to people’s lives, and it increases the possibility of an explosive eruption at the summit as explained in the image in the margin.

Heritage Futures researchers visited Hawaii in 2016. We met with our partner Jon Lomberg and discussed the ongoing conflict over the proposed Thirty Metre Telescope (TMT) with people on all sides of that discussion. We caught a glimpse of a different relationship to the future there, one that is continually rebuilt through connection and reconnection, rather than built once and preserved.

Some of this is apparent in attitudes toward the volcano, and the goddess of the volcano, Pele. As one person we spoke to described waiting to find if his house was in the path of lava ‘If she’s coming, she’s coming’. Obviously, many of the people who’s houses have been destroyed may feel differently, but the relationship with the lava is not a matter of bracing for impact. Residents watch, wait, react, and Hawaiians honour the goddess who brings this change.

People are calling it a disaster, if it’s a disaster to you then leave! You chose to live on the Hawai’i🌋 Island knowing there was an active volcano on it🔥 So if your house is destroyed don’t get mad because PELE lived there first, it’s her island not yours👏🏼

— khalia Kamalu (@KhaliaHoupo) May 16, 2018

Respect your ancestors. #Kilauea https://t.co/IYZImXDpHZ

— Lakota Law Project (@lakotalaw) May 12, 2018

I love how my family has magma one mile from their farm land and every time I talk to them they are just like, well it’s all up to Tutu Pele now.

— Maryam Hasnaa (@Maryamhasnaa) May 12, 2018

Heritage has a long relationship with volcanoes. Excavations at Pompeii were some of the earliest to capture the public imagination. Spectacular, well preserved sites from around the world are often called ‘the Pompeii of…’ as in the case of Must Farm a wetland site in Cambridgeshire dubbed ‘Britain’s Pompeii‘

The idea of daily life being ended and preserved at the same time is beguiling. Its easy to believe that the disaster creates a ‘snapshot’ and that this is a better representation of the past than slower forms of change. But we can tell stories with places that change more slowly too, ones that explore life unfolding.

Just as the processes through which living landscapes become heritage are complex and multiple, so too are the ways that volcanoes transform landscapes. Pompeii was destroyed by a ‘Plinian eruption’ (named for the historian Pliny who described it). Mt St Helen’s was also Plinian, but Kilauea is a Hawaiian eruption. There are even less dramatic eruption patterns known as Strombolian events, for the island of Stromboli where lava spatters constantly and small explosions happen many times an hour.

The draw of the disaster for heritage can extend into the way that the future is conceived. Risk and threat models for heritage management, whether for sea level change or development control rely on the notion that there will be an event, one that we can prepare for, predict monitor. But they deal less well with ongoing processes of change. This can also be seen in the image of the Doomsday clock. Originally framed as a metaphor for the threat of nuclear war, it is now used by some considering ‘tipping points’ in climate change

To be clear, we're not all gonna die–the global south is going to bear the brunt of the harm done. But the possibility of maintaining life-as-we-know-it is done for. At this point it's a question of how and when we're dragged kicking and screaming into humanity's next chapter.

— evelyn smith (@rageclit) May 16, 2018

Using narrative structures to understand change has its place but it can also keep us from working with change. Perhaps we can stop waiting for the Big One, stop thinking of heritage futures as a Plinian eruptions, and consider Hawaiian or even Strombolian change.