Dreaming with your eyes open

The glass jar containing the one and only good dream they had caught that day stood between them.The BFG, with great care and patience, was printing something on a piece of paper with an enormous pencil.

‘What are you writing?’ Sophie asked him.

‘Every dream is having its special label on the bottle,’ the BFG said. ‘How else could I be finding the one I am wanting in a hurry?’

The BFG, Roald Dahl

"When dreamers decide, for whatever reason, to share a dream experience, they choose an appropriate time and place, a specific audience and social context, a modality (visual or auditory), and a discourse of performance form."

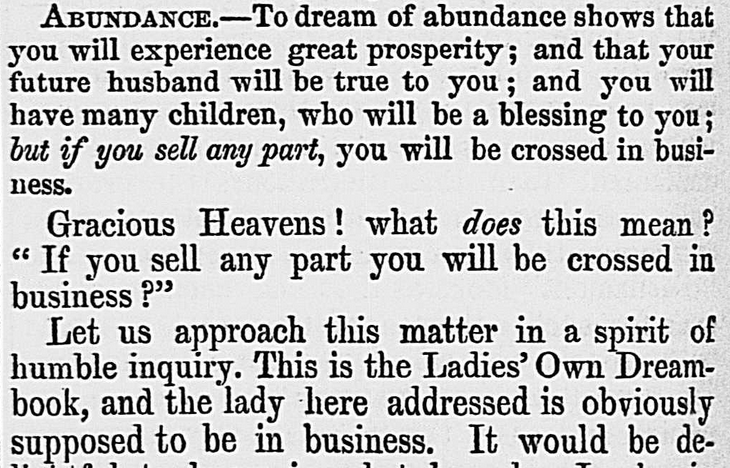

So wrote anthropologist of dreams, Barbara Tedlock, in an article published in 1991 in the journal Dreaming, the journal of the International Association for the Study of Dreams. I have just discovered this most wonderful of periodicals, and within it, such terminology I’d only dreamt of – “bizarreness”, a technical term that is the measure of the dream-weird – and aside from being a bountiful source of wonderment on a personal level, I, in the words of Robert Lowie (American anthropologist, student of Boas, and classifier of kinship systems), “a chronic and persistant dreamer,” have found it endlessly thought-provoking in light of the work I’m undertaking in the Diversity theme, on categorization.

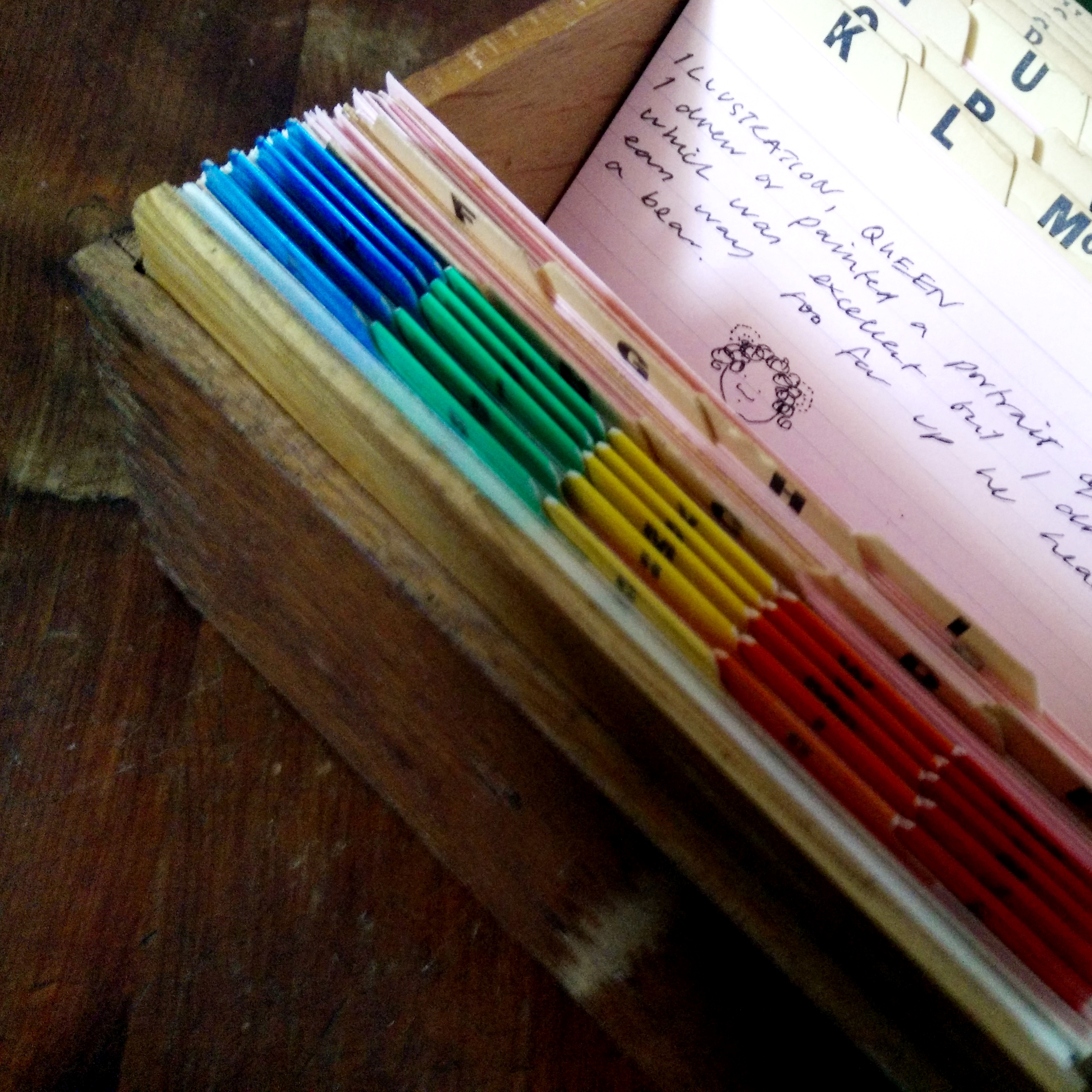

Indeed, that’s where it started. At our Knowledge Exchange event at the Royal Botanic Gardens, Kew, earlier in the year, the subject of personal collections came up a number of times. Many of the assembled group who worked daily with collections and categorizations expressed an arms-length attitude to the idea of maintaining collections “at home”. But over the days of the workshop, it emerged that a few of us – including the more vociferous collection deniers – gathered certain objects around a theme, but shied from the term collection. I own up to my collecting habits: it started with water and moved onto small gods and Elvisiana, and now, while I can load some of my hoarding proclivities into the category of interior design, one of my more serious collections is my own dreams. I’ve been collecting my dreams for years. Initially I wrote them in notebooks or diaries or just on scraps of paper, post-its – but amid other paper records, the collection fragmented.

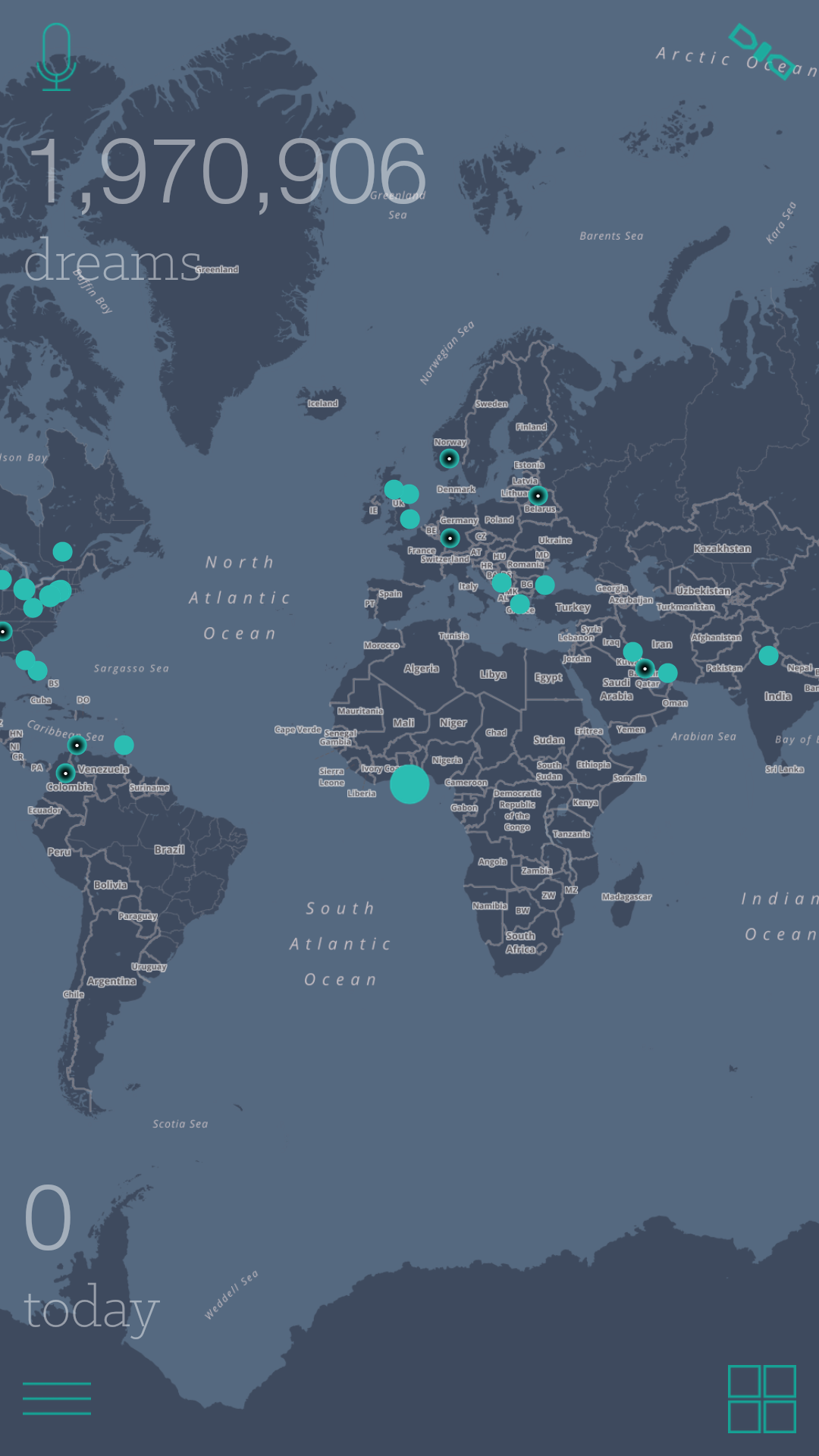

I began to write them on index cards and file them in a box, alphabetically by the most prominent theme. Now, I write them into Evernote. In between these two modes, I logged them into DreamSphere. DreamSphere is a downloadable app, very nicely designed, and more-or-less very nicely useable (though that glut of dreams from Cabo Verde represents the spot all novices drop the location pin in rather than prolific Atlantic dreamworlds). It also allows you to mine your dream content in a number of ways – statistical analysis (when do you dream, what are your most frequent themes, the emotional intensity of your dreams etc.); “orthodox” interpretations; and also the option to allow others to comment on or interpret your dreams for you. Until an unresolvable glitch made my place in it inaccessible, hence my migration to something more basic. The app is stalled now, on 1,970,909 dreams. But for a little while, I was weaving my dreams into a world-wide-web of dreamers.

In order to log a dream on DreamSphere, you dated it, wrote it, and chose pictorial keywords. If the word most suitable for your dream wasn’t there, you could submit it for addition to the global dream theme canon. And lo, I brought Poirot dreams and water polo dreams to the world. When you opened the app, a running count would tell you how many dreams had been logged in the world – in total, and on that day. It also told you how many people had dreamed the same dream as you. This was less alarming than it seems – should five of us have been influenced by Agatha Christie immersion, and submitted a dream with Poirot as a keyword, we would all have been categorized as dreaming the same dream. Further, it’s how the pros do it too. Says Calvin Kai-Ching Yu in his article on dream themes:

“There are, however, no two dreams which are exactly the same. Operationalizing the parameter as typical themes rather than typical dreams may therefore avoid those nnecessary debates as to how similar two typical dreams are or whether the “same” typical dreams have the same meaning. Instead of asking, for instance, whether two flying dreams belong to the same type of dreams, we simply acknowledge that the two dreams share the common theme of flying.”

It was all a dream. OR WAS IT?

Having discussed my dream collection with some of the Kew workshoppers, I was directed to Rebecca Lemov’s Database of Dreams: the lost quest to catalogue humanity. Lemov’s eloquent book documents Harvard psychologist Bert Kaplan’s attempt to build “the largest database of sociological information ever assembled”. Lemov devotes a chapter to Dorothy Eggan’s collection of Hopi dreams. Eggan collaborated with Kaplan, offering her dream collection as data, the potential of which she repeatedly claimed. Against the prevailing psychoanalytical view of the extreme subjectivity of dreams, Eggan hoped the dreams might be mined by researchers: on the cusp of cultural-domination by Western positivist media, they offered an avenue to the “universal” – reality wrestled in the sub/unconscious in a “scientifically graspable, quasi-statistical, and potentially global” process, that “as yet unknowable future methods” might unmask (Lemov 2015, 175).

Visualising dreams? Get a surrealist…

Graham Greene’s posthumously published dream autobiography A World of One’s Own – a selection of his dreams arranged as quasi life story – set up the private world of dreams against (following Hereclitus of Ephesus) the shared “Common World”. But he supported JW Dunne’s theories of precognition – offering his own dream-shipwreck on the night of the Titanic’s demise as one piece of evidence. Dreams as “scraps of the future as well as the past” (Greene 1992, xix). Jack Kerouac, in his foreword to his Book of Dreams also appealed to this universal private world: “And good because the fact that everybody in the world dreams every night ties all of mankind together shall we say in one unspoken Union” (Kerouac 1961, 3).

Happy Days, nightmare nights

In “The New Anthropology of Dreaming” Tedlock illustrates how anthropologists themselves, immersed in dreamwork in the field, underwent a transition period of transference and counter-transference in their own dreams, or in their reading of the dreams of the “other”, and quotes studies in which the manifest content of anthropologists’ dreams (in the field) swept back to their own origins, how they experienced dream-cultural-transition before arriving amicably in acceptance of the cultural heterogeneity of the self. She includes her own field experience of initiation into Zuni spiritualism, of her own dream of scuba-diving interpreted by their Zuni mentor as indicative of her coming success in spiritual training (172). She records that she continued to pay attention to dream meaning in accordance with her Zuni training.

It’s a curious notion. But a fantastical one as well. Imagine a global DreamSphere in which we don’t all dream of Poirot, or perhaps in which we do, but the figure of the wise little Belgian with the magnificent moustaches deliver multiply.

“Everyone has dreams.” Georges Perec stated on his own dreamworld, now published as La Boutique Obscure. “Some remember theirs, far fewer recount them, and very few write them down. Why write them down, anyway, knowing you will only sell them out (and no doubt sell yourself out in the process)? I thought I was recording the dreams I was having; I have realized that it was not long before I began having dreams only in order to write them.”

Perec’s is a statement related to the important observation of Tedlock’s that while dreams are private mental acts, which have never been recorded during their actual occurrence, dream accounts are public social performances taking place after the experience of dreaming.

“I thought I was recording the dreams I was having; I have realized that it was not long before I began having dreams only in order to write them.” Georges Perec

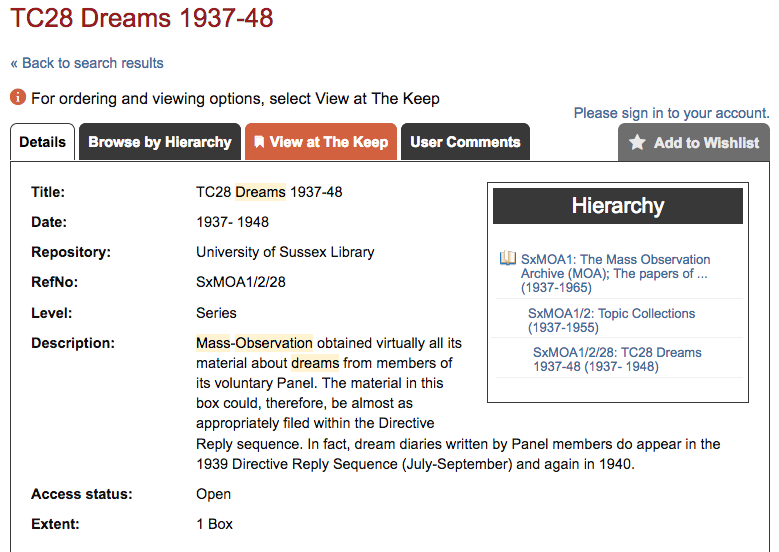

Dream accounts – the data of the unknowable act – are no longer ethnographic artefact, perhaps, but the archives? Boxes of visual modality, almost invariably text (though see Lemov’s own drawn interpretations of the Hopi dreams). The 500-odd dreams of the Mass Observation project are in one standard archive box at Sussex University. Eggan’s Hopi dreams were committed to Microcard. JB Priestley’s via-the-BBC collection of everyman-precognitive-dreams are in his archives held by the University of Bradford. All in boxes. In DreamSphere we are determined by text boxes, and inadequate keyword image boxes – themselves determined by text entries (though one does have the option to record in audio in DreamSphere – the essential option for the still half-asleep dreamer unable to engage to manual). The public social performance of our archives is hamstrung by our reliance on the tyranny of text. It strikes me, as it often does, that the structures of our archives, determined by the linearity of text, the linearity of shelving, limits what we might understand as the creative act of collecting. Collections do not form by themselves. The “modes of ordering” (Law 1994) we select determine, and eventually create, the way we understand the dream. “House arrest” is what Derrida calls it in Archive Fever: “the institutional passage from the private to the public” overseen by the archons, with their “publicly recognised authority”, their “hermeneutic right and competence”. The Mass Observation archive is a “Designated Collection”, so denominated by the Arts Council, opening up lines to further care, further funding. Apps like DreamSphere – hermeneutically situated in a dead corner of cyber-space – offer a crowd-sourced global-not-global archive, never to be designated, never going to be universal. And here is the analogue for any archive perhaps. The manifest content represents a world of its own. Its archive represents its house arrest. Dream(account)catchers only as good as we can imagine their operating systems.

Perec concludes:

“These dreams – overdreamed, overworked, overwritten – what could I then expect of them, if not to make them into texts, a bundle of texts left as an offering at the gates of the “royal road” I still must travel with my eyes open?”

References

Jacques Derrida. 1998. Archive Fever. University of Chicago Press

Calvin Kai-Ching Yu. 2015. One Hundred Typical Themes in Most Recent Dreams, Diary Dreams, and Dreams Spontaneously Recollected From Last Night. Dreaming. Vol. 25: 3

Barbara Tedlock. 1991. “The New Anthropology of Dreaming”. Dreaming. Vol. 1: 2

Rebecca Lemov. 2015. Database of Dreams: the lost quest to catalogue humanity. Yale University Press

John Law. 1994. Organising Modernity. Blackwell

Graham Greene. 1992. A World of My Own. Penguin

Georges Perec. 2013. La Boutique Obscure. Melville House

Jack Kerouac. 1961. Book of Dreams. City Lights