Taking the archive for a walk

An (Auto)Ethnography of an Archive

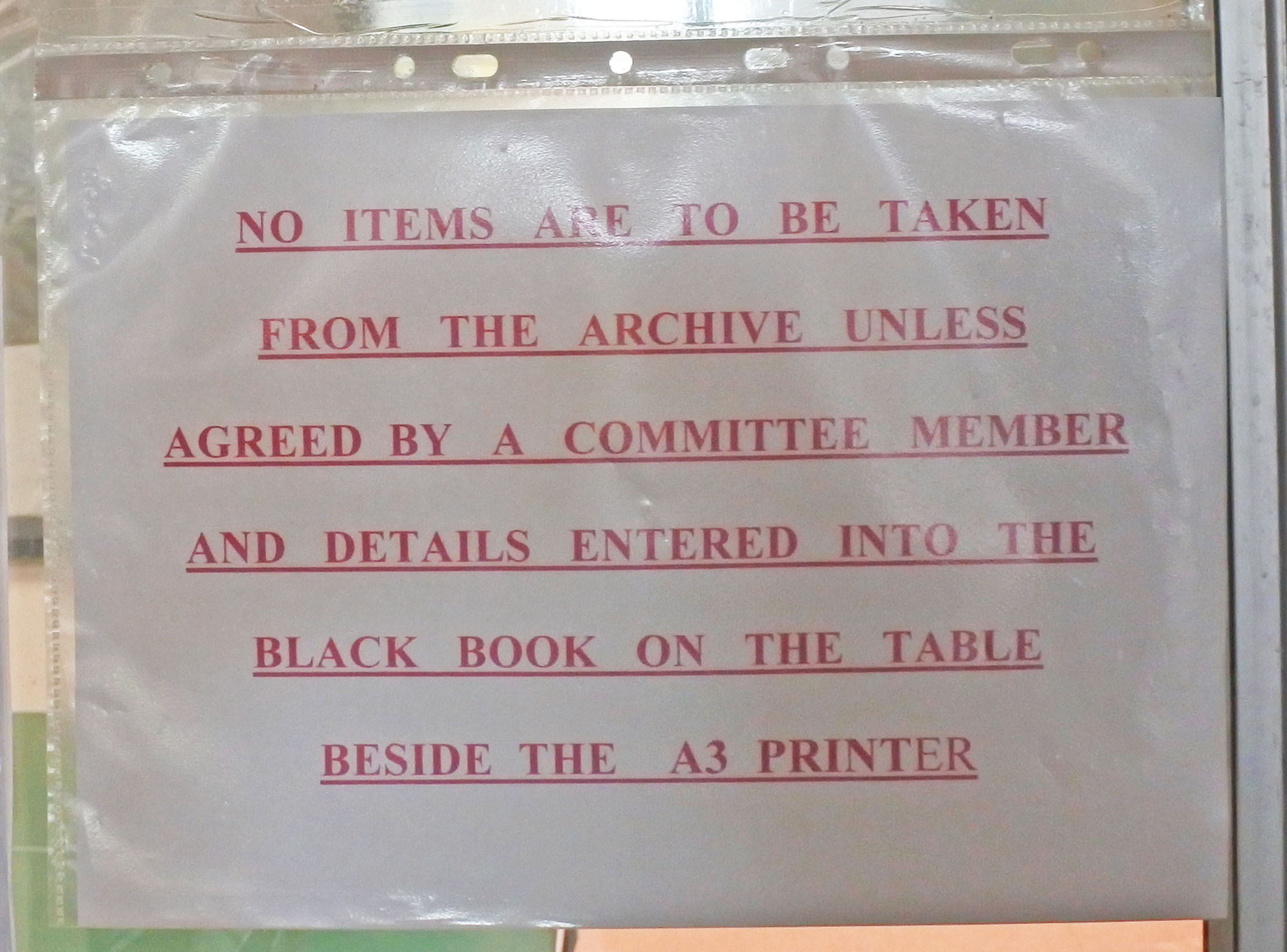

One of the methods that I have been using in my PhD research has been a kind of autoethnography. One day a week I have been taking myself off to a small hamlet just outside of St Austell, at the heart of Cornwall’s ‘Clay Country’, and carrying out historical research based in the China Clay History Society archives. Most of my time has been spent alone in a chilly archive room, poring over historical documents relating to the Blackpool Pit, a now disused china clay pit situated less than a mile from the very table at which I sit every week. Most of these documents have been assembled over the last 15 or so years by a dedicated group of volunteers, many of which I am fortunate enough to have the opportunity to get to know and informally interview about the reasons they continue to volunteer their time to collecting, managing and organising remnants of the declining industry.

Unlike many cultural or historical geographers working in the archive however, my main goal has not been to uncover a forgotten history or a stifled voice; by all accounts I am unlikely to uncover anything that society members don’t already know (and probably in better detail – some members are like living archives in themselves). I am instead using archival research as a method to try to better understand how the archive ‘works’, or inversely, how it sometimes does not. I am primarily interested in the practices and processes that shape an archive such as the China Clay History Society’s and the individual motivations that help build and shape heritage. To help me do this I have been keeping a field diary as I work through the archive material which documents my experiences of working in the archive and with the archive material itself. The obvious spillover from this method of working however is that over the course of my archival research I have also gathered huge amounts very specific specialist knowledge relating to one specific inactive china clay pit. And I never really knew what I was going to do with it. In order to give something back to the history society for so generously allowing me such unfettered access to their archive I had agreed to write one or two pieces for their quarterly newsletter, and, although not my main focus, the historical element has been a key anchor in this part of the research however I had struggled to conceive a practical application for all this ‘stuff’ I had been accumulating.

Running concurrently to my research however I became involved, through my supervisor Caitlin DeSilvey, in ‘Groundwork’, a project run by Cornubian Arts and Science Trust. Groundwork aims to bring international art and artists to Cornwall and make links with the regions rich social, economic, geological and artistic history, as well as its contemporary cultural life, through a series of fieldtrips and workshop events. Caitlin had offered to host one of these events in the clay country focusing on what can be found in the blank spaces on the map, which we decided, given the historical research I was working on, should take the form of a walk around the Blackpool Pit…

Taking the Archive Out

Fast forward to the 3rd of May 2017. A group of 14 artists, students and heritage professionals, assembled at the north gate of the Blackpool pit, in full high-vis completed with orange helmets and steel toe cap boots. Caitlin and I had planned the route to be anticlockwise and the story of the pit to be told in reverse chronology. Caitlin began the walk began ‘in the future’ and the group was lead through the landscape-cum-wasteland via a winding path right over the top of the main waste tip with complete silence from us as guides.

Walkers were encouraged to contemplate how the pit may be used in the future, with no explanation of its past, and the ways that nature and culture were interacting as the pit continued in state of industrial disuse. As the group approached the south side of Blackpool, circling round to the first full view of the water filled pit we began to transition into the past. Beginning with the most recent past I shared some details about the pits last operational day in 2007, gathered from the archival record and from interviews with former workers. Almost 600 jobs were lost at Blackpool in the year leading up to the closure. For many workers the closure of the pit was a highly emotional moment and the pit had been a part of clay mining in mid-Cornwall for so long that the loss of Blackpool was like “losing one of the family”:

I was there the last day it shut down… being there for 27 years, well I can’t describe it really… it was that bad just waiting for, I was day shift on that day so we left about 7 O’clock and then the night shift… just pressed the button and run down the pit and the refiner and that was that. (Mark, Interview 2017)

After a short pause for reflection the group continued the circumnavigation to the refining site, gathering outside the ‘Dynacone House’, believed to be one of the oldest buildings on the site, for a short overview of the pits recent history and of china clay mining in Cornwall since the 1950s. China Clay reached its peak in the 1980s and Blackpool was considered to be the flagship pit for English China Clays (ECC). A total of 10,000 tonnes of clay was extracted from Blackpool per week, resulting in about 90,000 tonnes of waste which found its way via an incline to the waste tip the group walked through at the beginning of the walk. Aerial photographs from the 1950s were on hand to show just how much the landscape has changed due to the intensive extraction that occurred post-war.

Continuing the walk ‘in to the past’ the group were invited to admire the view from the viewing platform, believed to have been constructed for a visit from the queen in the mid-1960s, whilst some historic maps of the area in the 1930s were passed around. One of the most interesting things to emerge from my archival studies is the rapid expansion of the Blackpool pit and its neighbour Great Halviggan, although today they are one in the same. Many smaller clay pits, and even some small villages found themselves subsumed as the industry expanded and bought out many of the smaller china clay producers. By its nature open cast extraction is destructive, smaller pits became part of larger pits that over time wiped out any trace that they ever existed: a sort of anti-palimpsest. The only traces left of these pits, Old Halviggan, Wheal Louisa, Noppies, and others, are in the archive documents.

As the walk continued back north we took one final stop alongside two historic sand tips to the east of the pit. By cross referencing current aerial photographs with maps from the 1880s and early 1900s, the historical pits of Carne Stents and South Halviggan, long since grown over can clearly be seen as deep green markers in the otherwise familiar agricultural landscape, although on the ground they are harder to locate. An account was shared of the Blackpool and Great Halviggan workers involvement in the infamous 1913 Clay Strike as well as details of the expansion of china clay during the later 1800s.

After an hour and half of travelling back in time the group arrived back at the North Gate. We concluded our walk in to past with final imagination of this landscape as it might have looked pre-1816, believed to be the first record of china clay extraction in this area, as upland moorland completely free from china clay, thereby completely filling in the blank space on the map.

*The author would like to thank IMERYS for generously allowing the group access to the Blackpool Pit and to members of the China Clay History Society, in particular Derek Giles, Ivor Bowditch, Eddie Best, Jenny Moore and an anonymous interviewee known as ‘Mark’, for kindly sharing their experiences and allowing access to the documents, maps and photographs that bring the history of Blackpool pit to life.