Creativity and Stewardship in Changing Landscapes

In May 2018, the Transformation Theme of the Heritage Futures project hosted a knowledge-exchange workshop in Cornwall. The event brought together a diverse group of people to talk about the role of the arts in landscape management and development activity in changing landscapes.

The setting for the workshop, mid-Cornwall’s china clay country, has seen many changes over the last 300 years, and it continues to change along with the clay industry and the surrounding communities. In dynamic landscapes like the clay country, process of transformation are often uneven and uncertain, and planning for the future while respecting the past and offering opportunities for community engagement can be challenging.

The unsettled character of such landscapes often draws creative practitioners to work in them; in some instances, such work is facilitated by organisations committed to long term, place-based curatorial involvement. Experimental creative practice can generate alternative perspectives on these ‘landscapes in limbo,’ and—in some contexts—open up new possibilities for heritage and art-based community engagement and economic development. Rarely, however, do creative practitioners and those responsible for landscape management and planning find themselves in dialogue. The workshop aimed to provide an opportunity for this dialogue to take place.

This knowledge-exchange workshop took place at Wheal Martyn Museum, one of our Heritage Futures partners. It was led by Caitlin DeSilvey and facilitated by Pete Whitbread-Abrutat of Future Terrains (a report on the workshop can be found here). Pete is an environmental specialist with over 25 years’ experience of natural resources management and sustainable development. Artists, industry representatives, curators, academics, heritage practitioners, land managers and others spent three days talking about how creative perspectives can help reframe problems as possibilities, and suggest new forms of stewardship for transitional places. Joff Winterhart’s drawn minutes of the event enabled us to ‘see’ our workshop as it unfolded, in a sequence of 71 ink sketches (see them here).

The Cornish Clay Landscape

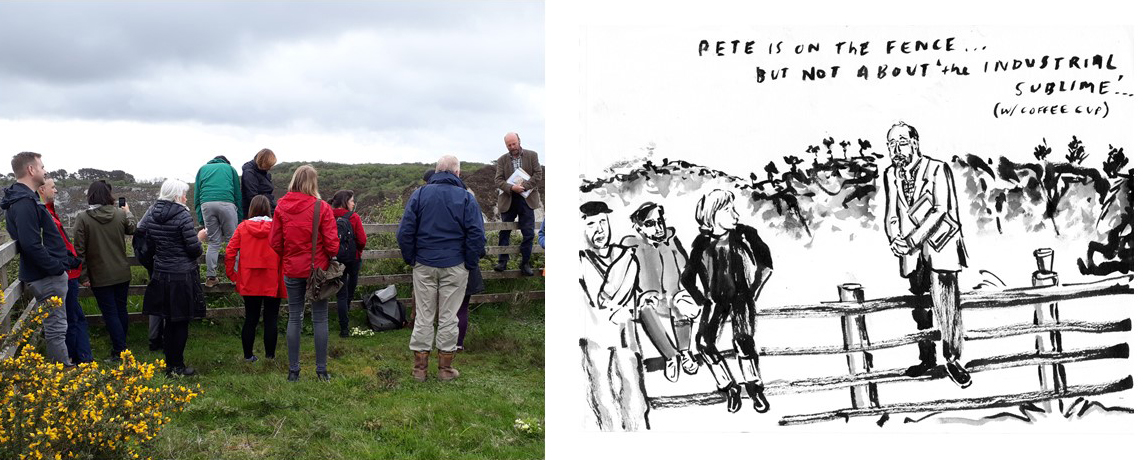

To familiarize the participants with the landscape shaped by the extraction of china clay (kaolin), a field trip took place on the second day of the workshop. The site visits were led by Sean Simpson, Imerys Business Development Coordinator, and Chris Varcoe, a retired Imerys employee who now works with Eco-Bos on the West Carclaze Garden Village development.

Other participants contributed to the conversation at different stops on the field trip to share their perspectives on the history and character of the landscape. At Baal Pit, Peter Herring from Historic England discussed how during the 18th century visitors to Cornwall perceived sites of mining and industry as awe-inspiring and beautiful, rather than ugly, and expressions of the romantic notion of the ‘industrial sublime’ (see Bristow 2015). Peter also shared a personal story about passing by the Sky Tip as a boy on his way to school and wondering about how it came to be there–seeding a curiosity about landscape that led to his career as an archaeologist.

On the other side of the road, the landscape surrounding the iconic Sky Tip prompted a conversation about the plans for the West Carclaze Garden Village development, which will retain the tip as the centrepiece of a residential development. In counterpoint, Heritage Futures creative researcher Antony Lyons discussed how the Sky Tip provides inspiration in assembling stories about the geology, social fabric, politics and imaginations of pasts, presents and futures.

To give the group some insight into how active industrial processes shaped the landscape over time, Chris and Sean showed us an operational clay pit at Littlejohns, one of the largest open-cast china clay pits in the world (see also the ITV website).

A visit to the redundant Blackpool Pit, on the other hand, led to an appreciation of both the complexity of accessing this non-operational site and the possibilities of future imaginaries. All workshop participants were required to conform to Imerys’s Health & Safety guidelines, and therefore to ‘suit up’ with personal protective equipment (PPE).

Blackpool Pit also featured some stunning views, with wild rhododendrons and other plants populating the revegetated landscape.

As they reflected on the new possibilities for recreation and public use emerging within the re-naturalised landscape, many of the participants pondered how one could creatively repurpose the post-industrial remnants spotted along the way, and address difficult issues of risk and liability.

After the field trip, the group returned to Wheal Martyn Museum to listen to presentations from fellow participants and engage in further discussion. Three afternoon sessions covered a range of themes, and included: reflections from land managers about integrating creative practice into their work; discussion of landscape-based curatorial projects and their long-term engagements with local communities; and sharing of examples of arts-led landscape performance in transitional places.

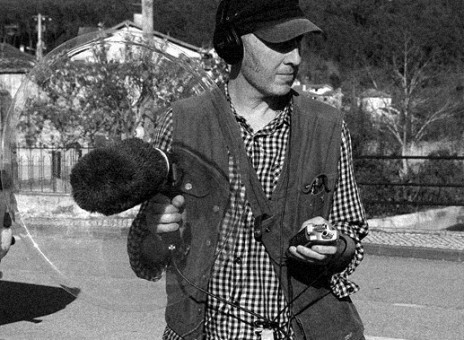

On the evening of 9 May, Wheal Martyn Museum hosted a pre-launch event for Antony Lyons’ ‘Limbo Landscape Lab’ exhibition. Friends of the museum and local area residents listened to a presentation from Antony previewing some of the film and audio work that will be included the exhibition, and browsed materials created by other workshop participants. Antony’s exhibition at Wheal Martyn Museum will run from 9 July to 22 Sept 2018. The exhibition format is a dynamic ‘project space’, and is part of the ‘Evening in Arkadia’ Arts Council-funded project.

Principles and Provocations

The last day of the workshop provided an opportunity for all the participants to discuss different ways of embedding creative approaches in conventional land management activities. The main points raised were collected in a draft ‘principles and provocations’ document.

One of the themes brought up in the conversation concerned the link between landscape and education. Schoolchildren used to learn about the area’s history and environment, including its mining industry, as part of their primary education, recalled one participant who grew up in Cornwall. Reflecting on her experience as a schoolteacher, she noted that changes to the national curriculum mean that this doesn’t happen anymore. She suggested that landscape/arts initiative could work with educators to explore regional histories in schools in both structured and informal ways.

Several participants commented on the need to keep an open mind, and not make assumptions about people’s attitudes and viewpoints. Because she works in a local council’s Historic Environment Service, she commented that people often assume she believes in protecting things in aspic. But, in reality, she and her team very willing to appreciate change and the need for adaptive re-use, in order for heritage to be relevant to communities in the future.

A land manager mentioned that one of the benefits of bringing in the arts and in taking a creative approach to the management of sites can be about disrupting narratives that assume a fixed and static place identity. As landscapes change, people may be encouraged to appreciate and understand that change is inevitable. But he also reflected on how important it is to understand people and their attachments a part of the changing landscape, not as separate. If their sense of place is changing – and if sense of place is essentially an extension of sense of self – then it’s understandable that people can feel destabilized by rapid landscape change.

Discussion also touched on approaches to landscape that don’t involve intervention or intensive management. One consultant on a local redevelopment project commented that some of the most diverse and interesting sites in the area are places where nature was left to its own devices after extraction ended. But even these ‘rewilded’ sites can require attention: for example, volunteer rhododendrons can carry diseases, and some light touch management may be needed to ensure that this doesn’t endanger other plants. In response to the discussion about letting nature take its course, one land manager commented that it is very difficult for humans not to intervene in landscape: “to let go of nature would be to let go of the self that is projected everywhere around it.”

Reflecting on the expectation that art can have a therapeutic benefits in communities, one artist indicated that she did not necessarily think that that is the artist’s job: “We can’t be responsible for making things better. I think what an artist can do is that they can go and give people the tools that they need to be resourceful to make those changes for themselves.” Conversation between the group suggested that the focus needs to be shifted from understanding the creative researcher as someone who delivers a solution to a problem to foster instead an appreciation for the unexpected and unpredictable ‘legacy’ of arts projects.

In response to a land manager mentioning that art isn’t a “branch of marketing”, one artist suggested that in reality, art-based landscape collaborations will usually have to be justified and written up in a report. If art is going to instrumentalised one way or another, he commented, then it is important to do so in ways that encourage dialogue and exploration of different scenarios and modalities, rather than reinforcing an artist/industry binary.

Finally, participants were asked how one could measure the success of creative, collaborative, landscape-based projects. A representative from the Eden Project shared some perspectives from their effort to measure the ‘personal impact’ of visits to the site through recording of conversations and interactions. She commented that evidence of personal impact also comes back to them through personal testimonies, conversations, emails, and images sent or shared online. Sometimes it comes back a week later, and sometimes it comes back years later. This raises issues about continuity, as a person must ‘stay in post’ long enough to enable these long-term engagements and conversations to mature. This can be a difficult ask for creative researchers, managers or academic researchers that may rely on funding regimes and short-term contracts.

These discussion points are simply snapshots of how the Transformation Theme worked through some of the challenges and opportunities involved in bringing together stewardship and creativity in transforming landscapes. It is clear from our workshop that more conversations between land management and artists/creative practitioners are needed to inform community engagement approaches and heritage policies and practices in the future.

[Artists] can’t be responsible for making things better. I think what an artist can do is that they can go and give people the tools that they need to be resourceful to make those changes for themselves.

References

Bristow,C. (2015) The Role of Carclaze Tin Mine in Eighteenth and Nineteenth Century Geotourism. In Hose, T. (Ed) Appreciating Physical Landscapes: Three Hundred Years of Geotourism. Geological Society, London, Special Publications, 471.

ITV website ‘First china clay pit in thirty years opens in Cornwall’, 29 June 2012. URL: http://www.itv.com/news/westcountry/2012-06-29/first-china-clay-pit-in-thirty-years-opens-in-cornwall/